The best year for movies since before the pandemic! In many ways, 2023 reminded me of 2019, in that my list was topped by two absolute masterpieces headed directly to my all-time Top 100 and almost-certain contenders for best of the decade.

If there was an interesting reoccurring theme in my favorite films this year, it was marriage. At least six of the below films deal directly with complicated marriages.1.

Killers of the Flower Moon (Martin Scorsese)

I will never hide my unabashed love and respect for Martin Scorsese and his films, and

Killers of the Flower Moon is yet another stunning achievement in the career of the world’s greatest filmmaker. Scorsese applies the meditative and reflective stylistic qualities of

Silence (2016) and

The Irishman (2019) to the largest possible canvas, in what amounts to his first western. Appropriately for a western,

Killers of the Flower Moon is a movie concerned with animals, either symbolically or literally - wolves, coyotes, buzzards, and, most hauntingly, owls. The two owl scenes in this movie send chills all the way up your spine.

As a portrait of the darkest depths of the human soul, this movie is unparalleled. Adapted from David Grann’s bestselling non-fiction book,

Killers of the Flower Moon tells the story of the oil-rich Osage people of Oklahoma in the 1920s, the wealthiest people per capita in the world… until cattle rancher William Hale (Robert De Niro) instigates a plan to murder the Osage, largely through intermarriage between white settlers and native women. With the husbands fatally poisoning their Osage wives, the “headrights” to the oil profits are passed on to the husbands, and slowly but surely, the wealth “flows in the right direction,” as Hale euphemistically puts it.

The relationship between Hale’s nephew Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio) and Mollie Kyle (Lily Gladstone), a member of the Osage Nation, is the heart of

Killers of the Flower Moon. By largely concentrating this epic film on the marital drama between Ernest and Mollie, Scorsese gives us a microcosm through which we can understand the larger betrayal of the Osage people by those they loved - and who, perversely, seemed to loved them. Particularly interesting to me are the ways in which Ernest is able to reconcile his horrible misdeeds. When Hale reveals to Ernest that Mollie had a first husband (despite Mollie having never directly admitted this to Ernest), he encourages his nephew to let her have her secrets - so Ernest can have his. After Mollie's first husband is murdered, Ernest asks Mollie how well she knew the man. When she doesn't mention anything about the marriage, you can see Ernest's inner moral compass rest easy - he can have his secrets, she can have hers (never mind that his secrets involve murdering her family). Scorsese is so talented at showing us the twisted logic by which morally compromised people are able to live with themselves (there's a great deal of this in

The Wolf of Wall Street, too).

One of the things I love most about what Scorsese has given us here is that we’re not always certain who knows what when, and this ambiguity places us in the mindset of Ernest. He certainly knows what’s going on, but because it’s not always laid out plainly to him (or he’s not privy to the full extent of the plan), he’s able to convince himself that everything’s fine. If Scorsese had his characters show all of their cards from the beginning, the audience wouldn’t really understand how Ernest is able to dupe himself, and his self-deception is critical to understanding our own complicity (again, not unlike

The Wolf of Wall Street).

De Niro is terrifying in a performance that embodies the banality of evil. His ability to manufacture grief in the aftermath of tragedies he’s orchestrated is chilling. More than once while watching his William Hale, I thought of De Niro’s Jimmy Conway from

Goodfellas (1990). The way Hale manipulates Ernest into protecting him in the third act brought to mind the famous line: “Your murderers come with smiles. They come as your friends, the people who've cared for you all of your life.”

Let me continue heaping praise on De Niro's work here (he is my favorite actor, after all). When Mollie reveals she's having another baby, it elicits one of Hale’s scariest reactions in the entire film. First, he looks at Ernest, who immediately gets unsettled by his uncle's silence. Then, after a rather muted reaction (in which so much is communicated by De Niro's non-verbal acting), he smiles, and says, "Blessings," cupping his hands slightly. Never before has "Blessings" been loaded with so much.

The final scene between Ernest and Mollie is absolutely devastating. This is the moment the entire film has been building to - Mollie confronting her husband and asking the one question he can’t bear to answer. It reminds me of Peggy Sheeran's simple question to her father in

The Irishman: "Why?" When Ernest utters his answer - which happens to be his last line in the film - is he lying to Mollie? Of course it’s a lie - but what I mean is, I think it’s a lie he comes to genuinely believe as the truth, because the alternative would be too horrifying to consider. Each time I view the film, it’s fascinating to observe the subtleties of DiCaprio’s performance. It’s tempting to think of his character as unintelligent, but I think it’s more nuanced than that.

Equally chilling is the final scene between Ernest and Hale. Never before have we seen Hale so vulnerable, so broken, while still being his conniving self. The way he tenderly tells Ernest he loves him, and then softly calls out "Don't throw it away, son" as Ernest turns his back on him is so beautifully acted. This scene could've so easily been Hale angrily lashing out at Ernest, but instead it's just pathetic.

There’s so much to cherish about this film - Thelma Schoonmaker’s editing (which gives the movie breathing room to let this story play out believably), Rodrigo Prieto’s cinematography, Jack Fisk’s production design (much like

Gangs of New York, they appear to have built an entire town for this movie) and Jacqueline West’s costumes. I am in awe of what Scorsese and his team have achieved here. But I must pay special attention to the music, which is always a hallmark of Scorsese’s pictures. And in this case, the late, great Robbie Robertson's final score for Scorsese may be his best (which is saying something, considering his score for

The Irishman is a knockout). The little guitar and harmonica riffs sprinkled in as Ernest, Hale and others scheme and plot against the Osage are absolutely terrifying (if you’re listening to the soundtrack, the track

Heartbeat Theme/ Ni-U-Kon-Ska is truly something special).

In addition to Robertson’s outstanding score, Killers of the Flower Moon is populated with Scorsese’s characteristically excellent use of existing music. The song Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground by Blind Willie Johnson is the backing for the film’s most bone-chilling sequence, in which Hale deliberately burns his own ranch for insurance money, and the hellish glow envelops Ernest as he "takes care" of Mollie in their bedroom. It's a truly expressionistic scene, where the flames outside the window look almost unreal (and indeed, it's doubtful the fire could be seen from Ernest and Mollie's house in town). The way Scorsese superimposes incandescent images of Hale's men in the field contorting their bodies (Scorsese describes it as “demons dancing around the fire, like the Witches’ Sabbath”) over Ernest drunkenly injecting his wife with poison is just astounding filmmaking. Another song, Where We’ll Never Grow Old by Alfred Karnes, adds significantly to the sadness of the scene in which Ernest is escorted away by federal agents after he decides not to testify against his uncle. Mollie watches Ernest through the kitchen window, as he grins and nods at her while being put in handcuffs (Ernest has assured Mollie he has the situation under control, and he seems to actually believe it). Ernest’s false bravado, the way Mollie looks at her husband, and the deep mournfulness of the music add up to a truly gutting sequence. Lastly, near the beginning of the film, there’s a haunting effect in using Bull Doze Blues by Henry Thomas to accompany still photographs of the Osage, their unsuspecting faces frozen in time. There’s an innocence in them that’s already being exploited by the street photographers overcharging the Osage for a simple photograph.

Killers of the Flower Moon is so many things: an incredible tribute to the Osage people, in which Scorsese, just as in

Kundun (1997), immerses you in the world of another culture; a big-screen epic that is astonishing to behold (of the four times I saw the movie in cinemas, the most impactful experience was in IMAX); the tenth entry in the greatest actor-director collaboration in cinema history (exactly 50 years after the release of Scorsese and De Niro’s first,

Mean Streets); a long overdue reckoning with America’s dark history of stolen land and stolen wealth. But, more than anything, it’s Martin Scorsese making the kind of film that other filmmakers can only dream of making. I am grateful to be alive to witness an artist of his caliber continuing to operate on a level unmatched by any director in film history.

One more note: there’s one small scene in particular that continues to haunt me. It’s an unnerving and surreal exchange between a hallucinating, bed-ridden Mollie and a possibly-imagined Hale, lording over her bed like the spectre of death:

Mollie (in Osage): "Are you real?"

Hale (smiles): "I could be real."

2.

Oppenheimer (Christopher Nolan)

Before seeing the film, I had heard folks compare Christopher Nolan’s

Oppenheimer to Oliver Stone’s

JFK (1991), and it’s an apt comparison - both movies provide an onslaught of information, all of it fascinating, not all of it easily decipherable after a first viewing. Nolan has always been great at building momentum, and

Oppenheimer is his most urgent and utterly propulsive movie yet - and also his best.

As an early birthday present, my mom and I made a pilgrimage to San Antonio to see

Oppenheimer in IMAX 70mm at the AMC Riverwalk, one of only two cinemas in Texas playing the film in Nolan’s preferred format. People had driven all the way from Mexico to see this presentation, and it was breathtaking. It was so heartening to see moviegoers embrace this dense, intellectually stimulating masterpiece, particularly those who made an effort to see it the way Nolan intended.

Among so many other things to praise about this film, I just have to say how happy I am that Robert Downey Jr. is back in meaty character roles. He’s outstanding in this film, and it’s my hope that one of the two Bobs (De Niro or Downey Jr.) walks home with this year’s Best Supporting Actor Oscar.

I was really struck by how experiential and impressionistic this film gets, particularly in its “first person” scenes (to use Nolan’s description of the color sequences, which are largely from J. Robert Oppenheimer’s perspective). Oppenheimer’s speech to the Los Alamos team shortly after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki is one of the most visceral, uneasy and jarring moments in all of the director’s movies. Nolan’s most memorable set pieces are usually action sequences; here, the film’s standout scene plays more like psychological horror.

My favorite part of

Oppenheimer is the mid-movie subsection about the Chevalier incident. Watching Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) sit down with Colonel Boris Pash (Casey Affleck) and attempt to report a potential security incident without implicating his friend is so incredibly tense (and Affleck is a legitimately unnerving presence, doing so much with limited screen time). Oppenheimer is trying to have it both ways - he wants to be a loyal American performing his patriotic duty by mentioning a treasonous approach by Chevalier while still managing to protect his friend’s identity. Murphy makes us feel the dueling instincts within Oppenheimer, and the tension in the scene comes from Oppenheimer’s rather slippery approach not going over well with hardened military men. It’s the film’s best articulation of Oppenheimer the free-thinking scientist versus Oppenheimer the loyal soldier.

In addition to Downey Jr. and Affleck, the supporting cast of

Oppenheimer is just phenomenal. Matt Damon may be the under-sung MVP of the film, Emily Blunt's third act takedown of the Atomic Energy Commission gets better with each viewing, and Gary Oldman, who probably has three minutes of screen time and only a handful of lines, makes a huge impression as Harry Truman. Every single part is so well-cast (welcome back, Josh Hartnett!), major and minor players alike. It's just a thrill to see such a talented ensemble bounce off each other for three riveting hours (which is a testament to Nolan's impeccable screenplay, which is now published in book form and truly a great read).

On a side note, in high school, I was in a production of

The Lovesong of J. Robert Oppenheimer (a little-known, absolutely fascinating play by Carson Kreitzer), and it was a thrill to reacquaint myself with these familiar characters (Rabi! Groves! Tatlock!) who sparked my imagination at a young age (I played Edward Teller, who’s portrayed here by Benny Safdie).

3.

The Holdovers (Alexander Payne)

The Holdovers is such a warm, deeply empathetic, generous movie, full of all the elements that make Alexander Payne’s films so moving and heartfelt. Payne creates a space you want to live in, and I cherished being able to spend winter break with these misfits. It’s a testament to how much I love Paul Giamatti’s performance that I forgive him for loudly talking during a movie (he has the absolutely wrong reaction to being shushed, but no matter - it’s the classic case of me being fascinated by a character who I wouldn’t be caught dead sitting next to during a movie).

This might be the perfect Christmas movie for the misanthropic, the curmudgeonly, the disillusioned middle-aged burn-outs. Yes, people can be awful - but every once in a while, they will surprise you, and it’ll melt your heart.

On a side note, there seems to be a narrative this awards season that Alexander Payne is "back" after the commercial and critical indifference to his last film

Downsizing (2017). This is disappointing because

Downsizing is absolutely fantastic - an ambitious, thoughtful movie that swings for the fences and continues to resonate as the climate crisis becomes more and more dire. I hold out hope that folks will come around to

Downsizing and eventually recognize it as the forward-thinking and deeply moving film that it is.

4.

Ferrari (Michael Mann)

Holy moly. I’m admittedly a die hard Michael Mann fan, but while I’ve admired his last few films (the Director’s Cut of

Blackhat is really strong),

Ferrari is his most focused and sharpest movie since

Collateral (2004).

For one thing, he’s dialed back the intensely digital photography just a bit (I mean, it’s still digital, but the frame rate has gotten back somewhere closer to normal). The film also features the director’s most compelling lead character since

Collateral, with Adam Driver lending a real emotional weight to the material. The interweaving of Ferrari’s personal life and professional life is beautifully done, and the racing scenes are dynamic as hell (Penélope Cruz is also amazing in this, and I’m surprised she hasn’t been factoring into the awards season conversation more).

What I love most is that Mann follows the Scorsese approach of “never explain.” We’re thrown into this world, we gradually come to understand the key relationships and conflicts, and what we don’t understand just makes us more engaged and fascinated by the material.

5.

Maestro (Bradley Cooper)

Bradley Cooper proves

A Star is Born (2018) was no fluke - this man is one hell of a filmmaker.

Maestro is the biopic done correctly - focusing not on the broad strokes of a career, but on the smaller, more intimate moments in between the professional milestones one can easily find on Wikipedia.

If the first hour is a rather overwhelming rush of lavish dinner parties and inside baseball talk among mid-century American artists, the second half of

Maestro slows down to a more somber portrait of a long, complicated marriage. Every scene between Cooper (as Leonard Bernstein) and Mulligan (as his wife, Felicia Montealegre) is so beautifully staged - there’s one that occurs in an Upper East Side apartment against an open window in which the Snoopy float from the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade drifts into frame at exactly the right time.

Perhaps it was my imagination, but did I spy Lydia Tár in Bernstein’s classroom near the end?

6.

Asteroid City (Wes Anderson)

In Wes Anderson’s

Asteroid City, there’s a moment so utterly bizarre and indescribable between Tom Hanks and Jason Schwartzman that it immediately dispels any notion of Anderson making puppets out of his performers. Within the carefully designed artifice, there is room for discovery on the part of the actors, yielding moments as totally unexpected as this.

I love that Anderson’s movies are becoming a bit more obtuse. It requires the audience to do a little more work to pull out the thematic meaning, as opposed to instantly revealing its cards. I don’t think it’s necessary to walk away from a movie having understood the entirety of its thematic content. The real question is, did you feel it? Did it conjure up something real and unique? With

Asteroid City, the answer to both, for me, is yes.

Upon a second viewing, I landed on my own interpretation of the material. The Actors Studio-esque drama class led by Willem Dafoe’s Saltzburg Keitel is representative of Anderson’s loyal company of actors who return and circulate for each of his films, and the film (or televised play, in the world of the movie) they’re attempting to make is a Wes Anderson film (

Asteroid City). But they’re not certain how to make it, or what it means, until they land on a repeated phrase that embodies the spirit of any of Anderson’s movies: “You can’t wake up if you don’t fall asleep.” In other words, only through artifice (or the dream world) can one truly awaken and learn about themselves.

Now, is any of this what Anderson intended? Probably not. But that’s the beauty of a movie that truly engages you and asks you to come to it, not the other way around.

While it’s true that Anderson’s filmmaking style has become a “brand,” of sorts (I heard a moviegoer ask the box office attendant for a ticket to “Wes Anderson” the same way one would ask for a ticket to “Indiana Jones”), it’s the best kind of brand in that it’s completely and utterly undesigned by a committee, but rather the unique creation of its maker’s interests and concerns. You can try to emulate Anderson’s aesthetic through AI all you want, but it won’t be able to predict the director’s obsessions with (in this case) mid-century American theatre and the anxieties of the Atomic Age.

7.

Anatomy of a Fall (Justine Triet)

What’s the difference between self-delusion and consciously deciding what to believe? That’s the dilemma faced by the eleven year-old boy who watches in horror as his parents’ marriage is deconstructed and held under a microscope in a court of law. No matter how closely we examine this marriage, though, we still don’t feel very close to the truth - whatever that is.

Justine Triet's brilliant Palme d'Or-winning Anatomy of a Fall exists in the murky grey areas that I find most compelling in cinema. The film is less concerned about whether or not Sandra (Sandra Hüller) is responsible for her husband's death than it is about the stories we tell ourselves to live with the absence of certainty.

8.

May December (Todd Haynes)

I saw Todd Haynes’s new film with a packed audience at the Austin Film Society Cinema, and the screening was followed by a Q&A with Richard Linklater and Haynes (the latter via Zoom). Boy am I glad I saw this with an audience - I wasn’t expecting

May December to be so uproariously funny, but it played to huge laughs. The scene where Natalie Portman’s character visits a high school drama class is hysterical.

There was an excellent New Yorker article two years ago titled

The Case Against the Trauma Plot, and it essentially argued that a good deal of modern cinema (and literature) is too neatly explaining away the eccentricities and flaws of complex characters by revealing some past trauma that’s somehow responsible for all of the character’s bad behavior. In the third act of

May December, Portman, playing an actress who is preparing to play a quite complicated real life woman, learns of a shocking traumatic event from the woman’s past that ultimately becomes her way into the character. The brilliance of Haynes’s film is that just when Portman thinks she has the character figured out, the real life woman reveals the traumatic event never happened. Ultimately,

May December is a darkly funny film about an actress attempting to tidily sum up the messiness of a real life situation for a bland indie movie that couldn’t be less interested in the unexplainable contradictions of human behavior. Haynes’s film, of course, is a much better movie, because it refuses to fall into the same trap.

9.

Dream Scenario (Kristoffer Borgli)

The new age of Nicolas Cage reaches perhaps its finest moment yet with

Dream Scenario, a film that harkens back to the great mid-budget Cage vehicles of the 2000s (

Adaptation,

Matchstick Men,

The Weather Man). Yes, the movie can be read as a meta commentary on Cage’s internet fame and the price of becoming ubiquitous - but it also morphs into something much darker and inarticulable with each passing scene. What’s most interesting is watching Cage’s character attempt to have agency in a situation where it’s absolutely impossible for him to exert any control. By the end, maybe he’s found a small way to alter the narrative, but only in the land of dreams. His real life is irreparably destroyed simply because of what other people project onto him. But the man doesn’t go down without a fight.

10.

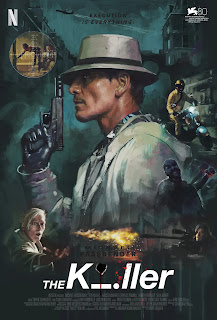

The Killer (David Fincher)

David Fincher’s

The Killer is a lean, darkly funny, no-nonsense thriller that makes for a thoroughly entertaining two hours at the cinema. Fincher imbues it with the unapologetic nihilism of

Killing Them Softly (2012), a film that shares some of the same ideas about American capitalism. But whatever loftier ambitions

The Killer might have - I’m sure one could expound at length as to what it’s really “about” - it’s first and foremost a really effective genre movie, complete with an insanely well-choreographed fight scene and some truly memorable sound perspective shifts.

Of course, there were more than ten great films released this year - here are ten more that I loved and admired:

The Zone of Interest (Jonathan Glazer)

Beau is Afraid (Ari Aster)

Air (Ben Affleck)

Personality Crisis: One Night Only (Martin Scorsese and David Tedeschi)

Mission: Impossible - Dead Reckoning Part One (Christopher McQuarrie)

Napoleon (Ridley Scott)

The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar, Poison, The Swan and The Rat Catcher (Wes Anderson)

Dreamin' Wild (Bill Pohlad)

American Fiction (Cord Jefferson)

Master Gardener (Paul Schrader)