Here are the ten movies from last year that most enraptured me:

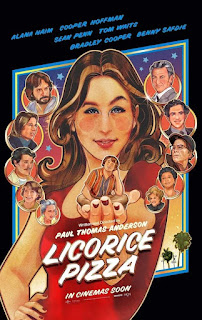

1. Licorice Pizza (Paul Thomas Anderson)

With Licorice Pizza, Paul Thomas Anderson has made one of the best films in recent memory. Like Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood (2019), the director creates a world in which you want to live – an unhurried, richly detailed portrait of a bygone era (specifically, San Fernando Valley in 1973) populated by idiosyncratic and colorful characters.

In a way, it feels like Anderson has made his version of a Richard Linklater film – except that Licorice Pizza is every bit as strange as any of Anderson’s other movies. I had no clue how individual scenes were going to unfold – every moment feels at once bewildering, spontaneous and thrillingly alive. As I write this, I’m realizing those are also apt ways of describing adolescence, which is at the core of Licorice Pizza.

The heart and soul of this film is the relationship between twenty-five-year-old Alana Kane (Alana Haim) and high school freshman and professional child actor Gary Valentine (Cooper Hoffman). The two characters form an intense connection in the film’s opening scene, set on school picture day, during which the smooth-talking Gary strikes up a conversation with Alana, who’s working as a photographer’s assistant. The whole sequence unfolds like a fairy tale, with Nina Simone’s beautiful July Tree accompanying Anderson’s unhurried long takes, in which he lets the naturalistic behavior of both leads take center stage.

Despite their age difference, there’s something almost telepathic about Alana and Gary’s connection. One of the strangest (and best) scenes in the film comes when Gary – jealous that Alana is going out with his friend Lance (Skyler Gisondo) – phones Alana at her house. Once she’s on the phone, he says nothing and quickly hangs up. Sensing that it was Gary, Alana calls him back. He answers. Not a word is spoken between them – just breathing coming from both ends. There is a cosmic sense of knowing in this silence – it’s as if the mere sound of each other’s breath brings them both a sense of calm. It’s never addressed again in the film, but the feeling of this moment lingers.

In the film’s official synopsis, Licorice Pizza is described as “the story of Alana Kane and Gary Valentine growing up, running around and falling in love in the San Fernando Valley, 1973.” As many others have noted, there’s a particular emphasis on the running around part. These are characters who love to roam about the Valley and exercise the freedom they have, and it makes for a very cinematic recurring visual motif.

But the running isn’t just random sprinting – it’s almost always Alana and Gary running back to each other. Throughout Licorice Pizza, both characters explore their own separate avenues, their paths diverging as they each navigate a turbulent world populated by truly bizarre (and not particularly trustworthy) adults. But whenever the crushing disappointment of the real world rears its head, Alana and Gary are always able to run back to each other. Nothing out there is like they think it is – auditioning for a movie, working for a local politician’s mayoral campaign, becoming an entrepreneur – and when things come crashing down, they represent something familiar to one another.

Licorice Pizza gets so much about adolescence right. It captures the boundless optimism and enthusiasm of being young, a time when you can seemingly throw yourself into anything. “Selling waterbeds? Why not! Maybe sell some pinball machines, too? Let’s try it!” “Maybe I’ll be an actress! Eh, that’s not so great. Oh, but working for a politician, that could be fun!” Alana and Gary’s identities aren’t set in stone, allowing them to bounce around in such a natural and carefree way, trying on different odd jobs and hobbies like hats. I loved how resourceful and mature these kids are – Gary, in particular, basically acts like a grown man. Outside of the opening scene, we never see him in school – he’s always involved in something seemingly beyond his years.

To be honest, I felt like an adult in high school, too. I thought I could handle all of the big emotions and responsibilities that life has to offer… but then, invariably, something you can’t see coming knocks you down and reminds you of just how little you know. And that’s when you run back to what you do know.

Early in his career, Anderson was often compared to Robert Altman, with Magnolia (1999) in particular owing a large debt to Short Cuts (1993). His more recent movies have veered away from the tapestry film structure, but Licorice Pizza feels like Anderson’s return to the ensemble picture, particularly in the way colorful periphery characters come entering and exiting the world of these adolescents, each of them fleshed-out and deeply vulnerable.

One minor character, in particular, feels like an Altman creation. When Alana goes to work for the mayoral campaign of city councilman Joel Wachs (Benny Safdie), she notices a suspicious-looking man (Jon Beavers) loitering outside the campaign office. Later, we see the same man at a restaurant, seated nearby Wachs and his long-suffering lover Matthew (Joseph Cross). The man’s presence is never explained, but we don’t really need an explanation. He reminded me of the unassuming, quiet assassin in Altman’s Nashville (1975) – except here, we don’t know what this character ultimately does. We can only guess his intention.

A special mention must go to Anderson’s use of music. Was there a more transcendent moment in cinema last year than when Alana and Gary lie down next to each other on a waterbed as Paul McCartney wails Let Me Roll It on the soundtrack? Some other strong contenders for the film’s best needle drop include Slip Away by Clarence Carter, Tomorrow May Not Be Your Day by Taj Mahal, Life on Mars? by David Bowie and Stumblin’ In by Chris Norman and Suzi Quatro. Each of these songs has a unique purpose, seemingly introducing us to a new phase of Alana and Gary’s lives.

And what can I say about the film’s amazing cast? Sean Penn, Bradley Cooper, Tom Waits, Christine Ebersole, Maya Rudolph, Harriet Sansom Harris and the entire Haim family make Licorice Pizza feel like a party. For that reason, along with many others, this is a movie I’ll be returning to again and again. After two years of nothing but bad news, Paul Thomas Anderson has put a much-needed spring in my step. (Of course, it didn’t hurt that, when first seeing the film in December, the post-screening Q&A with Alana Haim was scrapped and our audience was invited to an impromptu Haim concert at the Highball instead.)

Also, I’m sure this has been written somewhere by someone, but much better than the Marvel Cinematic Universe would be Anderson’s 1970s Los Angeles universe, where all the characters from Boogie Nights (1997), Inherent Vice (2014) and Licorice Pizza hang out and cross paths, and their children grow up to be the screwed-up adults in Magnolia.

2. Nightmare Alley (Guillermo Del Toro)

Guillermo Del Toro's Nightmare Alley is a film that has grown in my estimation with each viewing – and I’ve admittedly seen it a few times now, both in cinemas (where its gothic horror milieu is best experienced) and at home. I was surprised to feel so strongly about the film, as I admittedly didn't connect with Del Toro's prior, more acclaimed movie, The Shape of Water (2017). I have always admired the director's giddy enthusiasm for cinema and his talent for world-building, but, for whatever reason, his films (with the exception of Pan's Labyrinth) haven't been my cup of tea.

But here, Del Toro has made a film noir in its purest form. These are nasty characters with hearts of black coal, and the film admirably doesn't tell us how to feel about them. In one of his finest performances, Bradley Cooper weaponizes his charm and good looks to an unsettling degree. His Stanton Carlisle is a charlatan and a snake oil salesman – but he talks real good, and if he can charm the pants off Rooney Mara, what chance do the rest of us have?

It is a testament to the power of movie stars that we somehow morbidly continue to root for Stanton throughout Nightmare Alley, as he connives and schemes, blinded by ambition and narcissism, on a path to inevitable destruction and misery… and yet we can’t look away, holding out hope that this man might give in to his better angels.

I was in love with every detail of this film – the haunting ticking of Stanton’s stolen wristwatch; the long, unhurried scenes in which mood and character are placed center stage; the big movie star performances; the bygone world of carnies, freaks, geeks and mentalists. The score, by Nathan Johnson, conjures up dread at every moment, and yet Del Toro also knows when to be absolutely quiet, cutting out all unnecessary sound.

Nightmare Alley also had perhaps the most memorable final shot of any film last year – a close-up on Stanton, fully humbled and brought down to the filthy, stinking earth on which he’s spent the entire movie looking down. Cooper lets it absolutely rip in this shot.

In an ensemble packed to the gills with great performances, I’d like to single out Richard Jenkins as the low-key MVP. His Ezra Grindle is a frighteningly repulsive man, and yet Jenkins, with his inherent decency as an actor, somehow gets us to care when Stanton tricks Grindle and humiliates him. It’s one of many magic tricks Del Toro pulls off in Nightmare Alley, which has the audacity to eschew any platitudes about the triumph of the human spirit and acknowledge that, deep inside, a great deal of us are downright rotten to the core.

3. West Side Story (Steven Spielberg)

Nobody does it better than Steven Spielberg. I’ll admit I initially questioned the necessity of a remake of West Side Story, the spellbinding Broadway musical that was first adapted into a film in 1961 (winning ten Oscars, including Best Picture). But Spielberg (along with key collaborators, including screenwriter Tony Kushner and cinematographer Janusz Kaminski) makes this endeavor feel essential from the first frame to the last. This is a big, colorful and emotionally wrenching time at the movies.

On New York’s Upper West Side in the 1950s, two street gangs are engaged in a turf war – the Jets, comprised of second and third generation Irish and Italian Americans, and the Sharks, who are largely Puerto Rican. The two gangs are stand-ins for the Montagues and Capulets of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, and the star-crossed lovers from opposite sides who further escalate the gangland conflict are Tony (Ansel Elgort) and Maria (Rachel Zegler). After a chance encounter at a local dance, the two fresh-faced teenagers fall head over heels for one another – incensing both gangs in the process. Maria’s brother Bernardo (David Alvarez), the leader of the Sharks, meets with Riff (Mike Faist), the leader of the Jets, to discuss the terms of a “rumble” – a planned, violent confrontation between gangs that, as anyone who has read Romeo and Juliet knows, does not exactly set the course for Tony and Maria’s happily-ever-after.

The aforementioned “rumble,” which occurs about two-thirds of the way through West Side Story, is one of the most astounding and electric set pieces of Spielberg’s career. It doesn’t matter if you know the outcome. It is harrowing and tense, and one of the most memorable scenes in any movie last year.

This West Side Story is especially effective as an illustration of how two groups can be pitted against one another, each thinking the other is responsible for their disenfranchisement, while the real perpetrators (in this case, the City of New York clearing the neighborhood for what will become Lincoln Center) remain above the chaos. Spielberg and Kushner have made some fascinating changes to the source material in this regard. The presence of Puerto Ricans is not what’s causing the Jets’ disenfranchisement (that would be growing up without parents and role models, as articulated in the number Gee, Officer Krupke), but anti-immigration sentiment serves as an easy outlet for their rage and feelings of victimhood.

But these changes don’t feel like Spielberg and Kushner trying to make the story more “relevant” for a modern audience; instead, they’re taking thematic strands that have always been a part of this story’s text and fleshing them out in a way that resonate even more. After all, West Side Story was a musical that tackled nativism and class divisions long before those ideas were prevalent in mainstream musicals.

It’s a particular thrill to watch Spielberg wield his visual wizardry in a movie musical. Most of his contemporaries – Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Woody Allen, Robert Altman – have made big-screen musicals to varying degrees of success, but Spielberg’s sensibilities are perhaps the most in-tune with the showmanship needed to craft a memorable musical. West Side Story is another jewel to add to the director’s incredibly varied 21st century filmography, which has tackled startling visions of the future (Minority Report), reckonings with vengeance (Munich), whimsical comedy-drama (Catch Me If You Can, The Terminal), pure popcorn entertainment (The Adventures of Tintin, Ready Player One) and, perhaps most profoundly, detailed portraits of American history (Lincoln, Bridge of Spies, The Post).

4. Don’t Look Up (Adam McKay)

“We really did have everything, didn’t we?”

This is Adam McKay's best film. It'd be one thing if the entire movie felt like a lecture (I love Vice and The Big Short, but both films admittedly slip into this tendency) - but there is real emotional heft to this thing.

At first glance, it appears the entire film may be Leonardo DiCaprio and Jennifer Lawrence exhaustively warning the powers-that-be of an impending natural disaster. But then McKay turns it in an interesting direction – DiCaprio's character gets attracted to the limelight and is subsequently caught up in the media frenzy, leaving Lawrence on the sidelines as the pouty doomsday girl. One of the more emotionally affecting scenes in the film is straight out of Sidney Lumet's Network (1976) - DiCaprio's wife (Melanie Lynskey) confronts him in a hotel room about his infidelities with Megyn Kelly-lite (Cate Blanchett). And, just as William Holden does to Beatrice Straight in Lumet's film, DiCaprio brutally cuts ties with his devoted spouse in favor of a relationship with a more exciting and utterly vapid creature of television.

Even the characters who are on the side of science get distracted by the more entertaining news dominating the airwaves – the break-up of a music power couple, the President's illicit affair with her good ole boy Supreme Court appointee, the launch of a new smartphone. This is the world we've created.

Ultimately, Don't Look Up leaves us with an appropriately icky feeling. All of the exasperation, laughter, frustration and anger (both on our and the characters' parts) gives way to the inevitable – the ultimate silencer, in which all of the politicians, scientists, news pundits and comet-deniers meet the same indiscriminate fate (well, except for the shuttle that launches the President and other high-profile dignitaries into space before the impact). This final sequence – in which, yes, the world indeed ends – culminates in a moving dinner amongst the level-headed astrologists. While they choose to spend their final moments breaking bread with family, everyone else is panicking, the reality of the situation finally catching up to them. Of course, it's too late.

Here is a great example of a filmmaker getting maximum mileage out of his all-star ensemble. Too many films with packed casts invariably waste the talent involved – but here, every big name gets ample opportunity to showcase their range. In particular, DiCaprio is wonderful, working in a comedic mode of which we're thankfully getting to see more and more. Other standouts include Meryl Streep as the Trump-ian President and Mark Rylance as a socially inept tech billionaire (who seems to have trouble even being in the same room as other people).

On a side note, the critical reception of Don’t Look Up was ridiculously disheartening. Not since Alexander Payne's Downsizing (2017) has a go-for-broke film received such a muted, outright dismissive response from film critics, and it’s been particularly bizarre watching far less ambitious and interesting titles somehow pass the critical litmus test with flying colors.

5. The Tragedy of Macbeth (Joel Coen)

My nearly sold-out cinema burst into applause as soon as Joel Coen’s The Tragedy of Macbeth ended – which is notable considering that it was a crowd of folks who had gathered at 9:30pm on a Monday night to experience a black-and-white Shakespeare adaptation.

So, yes, this film is impeccably well-made. What's always astonishing about well-performed Shakespeare is how we understand the meaning of a scene not necessarily through total comprehension of every line, but through the feeling and delivery of the language. It really doesn't matter if you understand everything you hear – the dramatic purpose of a scene is always resoundingly clear and the internal struggles of the characters tangibly real.

With The Tragedy of Macbeth, Coen offers a nightmarish vision to accompany the text – the Bergman-esque imagery of his adaptation will stay with me for a long time. As always, the acting is superb. Marvel at the way minor Shakespeare characters are molded into colorful ancillary Coen creations (played by the likes of Stephen Root and Jefferson Mays). And where's the talk of Denzel Washington winning his third Oscar? It is a thrill seeing the actor tear into this role with all of his prowess. Give Washington free rein with the text of Shakespeare, August Wilson, Eugene O'Neill or Malcolm X and you'll get the finest acting on earth.

6. The French Dispatch (Wes Anderson)

Wes Anderson's The French Dispatch is the only movie I can recall that’s structured in the form of a literary magazine (complete with an opening obituary, an on-the-town briefing by a cycling Owen Wilson, and three feature stories from noted Dispatch journalists). Heck, there's even a cartoon section near the end of the film. Above all, this is a moving love letter to a ragtag team of expatriates who have found a home abroad in Ennui-sur-Blasé, France – far away from the magazine's base in Liberty, Kansas.

The most moving scene in the film involves Stephen Park’s Lt. Nescaffier, the personal chef to the Police Commissioner, musing aloud to journalist Roebuck Wright (Jeffrey Wright) about the reasons they both left their homelands to seek something else in France. The exchange was nearly cut out of Roebuck's piece, but French Dispatch editor Arthur Howitzer Jr. (Bill Murray) insists he include it. Not only is the scene the crux of Roebuck's article, it's also the emotional glue that holds the film together, bringing the thematic focus into clear sight.

As always with Anderson’s films, there’s an undercurrent of melancholy to every scene – a wistfulness buried beneath the staggering amount of visual information and gags packed into each frame (I always experience sensory overload when watching an Anderson film, never more so than with The French Dispatch). And the formal inventiveness never stops for a moment. One of my favorite bits is Roebuck’s journey through the labyrinth police station, in which he simultaneously addresses the audience and tries to figure out where the hell he is. The scene feels like a deconstruction of direct-address long-takes, in which a character leads us through a new world.

Another favorite: in the film's first story, titled The Concrete Masterpiece, writer J.K.L. Berensen (Tilda Swinton) stops midway through her lecture on the work of incarcerated artist Moses Rosenthaler (Benicio del Toro), crosses downstage and utters a series of revelations about Rosenthaler so disconcerting that it completely changes the tone of the scene. I’ll have to see the film again to pinpoint exactly what Anderson is doing here, but it caused an audible shift in my cinema audience.

All of the actors are wonderful here – particularly Wright and Murray, who share a scene late in the film that powerfully illustrates the protective home Howitzer Jr. has provided for his journalists.

7. The Last Duel (Ridley Scott)

Between The Last Duel and House of Gucci, Sir Ridley Scott truly outdid himself in 2021.

The Last Duel, in particular, races forward with narrative purpose. It’s an enormously entertaining portrait of contradictory perspectives, unreliable narrators and wounded machismo – dramatized on a characteristically enormous canvas by Scott. Matt Damon, Jodie Comer, Adam Driver and Ben Affleck are as excellent as you’d expect, and the script – by Damon, Affleck and Nicole Holofcener – inventively sidesteps every expectation of this kind of film.

In a just world, The Last Duel would have been one of the biggest hits of the fall. Go support good movies, people!

8. C’mon C’mon (Mike Mills)

Absolutely lovely. C’mon C’mon is the kind of film to get lost in, with its series of small moments resulting in a cumulative power that’s hard to shake after leaving the cinema. Mike Mills is three-for-three after Beginners (2011) and 20th Century Women (2016), and Joaquin Phoenix is utterly beguiling in one of his best and most natural performances. His character’s relationship with his nephew (a wonderful Woody Norman) is heartwarming in its sincerity.

A few scenes that touched me deeply: Norman asking Phoenix why he’s not married, and the way Phoenix responds by dipping in and out of the bedtime story he’s reading to his nephew, ultimately admitting he doesn’t know why his last relationship ended; Phoenix’s reaction upon learning his sister had an abortion; Norman’s immense sadness upon realizing he won’t remember most of his travels with his uncle by the time he gets older.

It’s true – I don’t remember many of the specifics of the times I spent with loved ones at a young age. But I remember exactly how they made me feel, and what they meant to me in that moment. That’s what carries on.

9. The Card Counter (Paul Schrader)

For William Tell (Oscar Isaac), there are two possible paths – one of salvation, and one of continued destruction.

The scenes between William and Cirk (Tye Sheridan) are among the best written exchanges of Paul Schrader’s career. There’s a constant dance happening between these two, as William considers following through with Cirk’s proposal to capture and torture Colonel Gordo (Willem Dafoe), the architect behind the atrocities committed against prisoners at Abu Ghraib. William has ample reason to choose this path – Gordo suffered no consequences for his actions, while William, who served under him, was sentenced to military prison. The temptation for vengeance is muted only by William’s impulse to take Cirk under his wing and guide him on the right path.

Schrader doesn’t victimize William in the slightest – yes, Gordo was the mastermind of the crimes at Abu Ghraib, but our hero unambiguously tortured prisoners. The question now is, does he continue down that path, or find some form of penance?

One thing I love about The Card Counter is that it’s not about poker in an abstract sense – the specifics of the high stakes card-playing world fill every scene. Most movies nowadays choose to simply indicate – as if the filmmaker were saying, “You won’t understand this complicated profession, so just trust us that our character is good at what he does.” But by giving us access to William’s inner life (largely through the character’s private journaling, which comfortably places The Card Counter among Schrader’s other man-in-a-room-writing-down-his-thoughts masterworks), the filmmaker allows us to understand exactly how this man does what he does, how he learned it, and how it informs his every move.

There’s a brilliant moment near the end of the film in which William plays opposite an overly patriotic poker player. I kept waiting for Schrader to show us William’s hand, but he doesn’t – instead, he simply lets the scene play out on the actors’ faces. At this point, we understand enough about William’s methods that we don’t even need to see the cards.

From the get-go, Robert Levon Been and Giancarlo Vulcano's score kept me in a heightened state of anxiety. Part of the pleasure of The Card Counter is having no idea where the film is going to go – while somehow also knowing exactly how things could go, and dreading that worst-case-scenario outcome for William.

On another formal note, I continue to find Alexander Dynan's cinematography for Schrader remarkably pleasing to the eye. Like First Reformed (2018), the camera movement and blocking of actors feels inspired by a Bresson movie from the 1950s, and yet the picture is unabashedly digital-looking, which for whatever reason makes every frame slightly unsettling (unlike First Reformed, which was 4:3, The Card Counter is a little bit wider at 1.66:1).

10. Last Night in Soho (Edgar Wright)

A second viewing really added to the experience on this one. The first time around, I was startled and disturbed by the film's excellent depiction of London's seedy underbelly, particularly in a mid-movie sequence that dips beneath the glamour of the dance floor and puts the full ugliness of this world on display.

I was less certain on first viewing exactly where director Edgar Wright was taking us, at least for the film's first half. Watching it again, I delighted in picking up on Wright’s masterfully-planted clues and got a certain kind of pleasure knowing exactly where this thing was heading. This allowed me to live in the world of the film a bit more – and what a world it is! The seediness aside, Last Night in Soho is an absolute blast of visual and musical delights. Wright has a ton of fun playing around with genre and the milieu of 1960s London. There were more than a few big, drab-looking movies released in cinemas last fall, but Last Night in Soho, in contrast, was full of life and color, not to mention genuine tension and menace.

I greatly admire Edgar Wright's work, but some of his films are almost a little too hip or self-reflexive for me (particularly Scott Pilgrim vs. the World – a movie I fully recognize is well-done, but most of the video game references are lost on me). But here, he's wrestling with larger ideas (romanticization of the past and mental illness among them) and dealing in pure genre territory (Last Night in Soho is fun, but it's not particularly funny – there are few comedic gags to be found). I guess what I'm saying is... this is my favorite Edgar Wright movie thus far, and it deserved to be a much bigger hit.

Special Jury Prize

Pretend It’s A City (Martin Scorsese)

This isn’t technically a film, but it’s too much of an absolute joy to not mention. In addition to being a delightful portrait of Fran Lebowitz and New York City, you can also play a fun game of Where’s Waldo with me in the audience, grinning like the exhilarated 22-year-old I was (specifically in Episode 6, Hall of Records). Does this count as being in a Martin Scorsese film?

I never knew if this footage would see the light of day – but here it is, put together beautifully. Watching Scorsese and Lebowitz peruse the New York Public Library makes one long for a buddy movie starring these two.

1. Licorice Pizza (Paul Thomas Anderson)

With Licorice Pizza, Paul Thomas Anderson has made one of the best films in recent memory. Like Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood (2019), the director creates a world in which you want to live – an unhurried, richly detailed portrait of a bygone era (specifically, San Fernando Valley in 1973) populated by idiosyncratic and colorful characters.

In a way, it feels like Anderson has made his version of a Richard Linklater film – except that Licorice Pizza is every bit as strange as any of Anderson’s other movies. I had no clue how individual scenes were going to unfold – every moment feels at once bewildering, spontaneous and thrillingly alive. As I write this, I’m realizing those are also apt ways of describing adolescence, which is at the core of Licorice Pizza.

The heart and soul of this film is the relationship between twenty-five-year-old Alana Kane (Alana Haim) and high school freshman and professional child actor Gary Valentine (Cooper Hoffman). The two characters form an intense connection in the film’s opening scene, set on school picture day, during which the smooth-talking Gary strikes up a conversation with Alana, who’s working as a photographer’s assistant. The whole sequence unfolds like a fairy tale, with Nina Simone’s beautiful July Tree accompanying Anderson’s unhurried long takes, in which he lets the naturalistic behavior of both leads take center stage.

Despite their age difference, there’s something almost telepathic about Alana and Gary’s connection. One of the strangest (and best) scenes in the film comes when Gary – jealous that Alana is going out with his friend Lance (Skyler Gisondo) – phones Alana at her house. Once she’s on the phone, he says nothing and quickly hangs up. Sensing that it was Gary, Alana calls him back. He answers. Not a word is spoken between them – just breathing coming from both ends. There is a cosmic sense of knowing in this silence – it’s as if the mere sound of each other’s breath brings them both a sense of calm. It’s never addressed again in the film, but the feeling of this moment lingers.

In the film’s official synopsis, Licorice Pizza is described as “the story of Alana Kane and Gary Valentine growing up, running around and falling in love in the San Fernando Valley, 1973.” As many others have noted, there’s a particular emphasis on the running around part. These are characters who love to roam about the Valley and exercise the freedom they have, and it makes for a very cinematic recurring visual motif.

But the running isn’t just random sprinting – it’s almost always Alana and Gary running back to each other. Throughout Licorice Pizza, both characters explore their own separate avenues, their paths diverging as they each navigate a turbulent world populated by truly bizarre (and not particularly trustworthy) adults. But whenever the crushing disappointment of the real world rears its head, Alana and Gary are always able to run back to each other. Nothing out there is like they think it is – auditioning for a movie, working for a local politician’s mayoral campaign, becoming an entrepreneur – and when things come crashing down, they represent something familiar to one another.

Licorice Pizza gets so much about adolescence right. It captures the boundless optimism and enthusiasm of being young, a time when you can seemingly throw yourself into anything. “Selling waterbeds? Why not! Maybe sell some pinball machines, too? Let’s try it!” “Maybe I’ll be an actress! Eh, that’s not so great. Oh, but working for a politician, that could be fun!” Alana and Gary’s identities aren’t set in stone, allowing them to bounce around in such a natural and carefree way, trying on different odd jobs and hobbies like hats. I loved how resourceful and mature these kids are – Gary, in particular, basically acts like a grown man. Outside of the opening scene, we never see him in school – he’s always involved in something seemingly beyond his years.

To be honest, I felt like an adult in high school, too. I thought I could handle all of the big emotions and responsibilities that life has to offer… but then, invariably, something you can’t see coming knocks you down and reminds you of just how little you know. And that’s when you run back to what you do know.

Early in his career, Anderson was often compared to Robert Altman, with Magnolia (1999) in particular owing a large debt to Short Cuts (1993). His more recent movies have veered away from the tapestry film structure, but Licorice Pizza feels like Anderson’s return to the ensemble picture, particularly in the way colorful periphery characters come entering and exiting the world of these adolescents, each of them fleshed-out and deeply vulnerable.

One minor character, in particular, feels like an Altman creation. When Alana goes to work for the mayoral campaign of city councilman Joel Wachs (Benny Safdie), she notices a suspicious-looking man (Jon Beavers) loitering outside the campaign office. Later, we see the same man at a restaurant, seated nearby Wachs and his long-suffering lover Matthew (Joseph Cross). The man’s presence is never explained, but we don’t really need an explanation. He reminded me of the unassuming, quiet assassin in Altman’s Nashville (1975) – except here, we don’t know what this character ultimately does. We can only guess his intention.

A special mention must go to Anderson’s use of music. Was there a more transcendent moment in cinema last year than when Alana and Gary lie down next to each other on a waterbed as Paul McCartney wails Let Me Roll It on the soundtrack? Some other strong contenders for the film’s best needle drop include Slip Away by Clarence Carter, Tomorrow May Not Be Your Day by Taj Mahal, Life on Mars? by David Bowie and Stumblin’ In by Chris Norman and Suzi Quatro. Each of these songs has a unique purpose, seemingly introducing us to a new phase of Alana and Gary’s lives.

Also, I’m sure this has been written somewhere by someone, but much better than the Marvel Cinematic Universe would be Anderson’s 1970s Los Angeles universe, where all the characters from Boogie Nights (1997), Inherent Vice (2014) and Licorice Pizza hang out and cross paths, and their children grow up to be the screwed-up adults in Magnolia.

2. Nightmare Alley (Guillermo Del Toro)

Guillermo Del Toro's Nightmare Alley is a film that has grown in my estimation with each viewing – and I’ve admittedly seen it a few times now, both in cinemas (where its gothic horror milieu is best experienced) and at home. I was surprised to feel so strongly about the film, as I admittedly didn't connect with Del Toro's prior, more acclaimed movie, The Shape of Water (2017). I have always admired the director's giddy enthusiasm for cinema and his talent for world-building, but, for whatever reason, his films (with the exception of Pan's Labyrinth) haven't been my cup of tea.

But here, Del Toro has made a film noir in its purest form. These are nasty characters with hearts of black coal, and the film admirably doesn't tell us how to feel about them. In one of his finest performances, Bradley Cooper weaponizes his charm and good looks to an unsettling degree. His Stanton Carlisle is a charlatan and a snake oil salesman – but he talks real good, and if he can charm the pants off Rooney Mara, what chance do the rest of us have?

It is a testament to the power of movie stars that we somehow morbidly continue to root for Stanton throughout Nightmare Alley, as he connives and schemes, blinded by ambition and narcissism, on a path to inevitable destruction and misery… and yet we can’t look away, holding out hope that this man might give in to his better angels.

I was in love with every detail of this film – the haunting ticking of Stanton’s stolen wristwatch; the long, unhurried scenes in which mood and character are placed center stage; the big movie star performances; the bygone world of carnies, freaks, geeks and mentalists. The score, by Nathan Johnson, conjures up dread at every moment, and yet Del Toro also knows when to be absolutely quiet, cutting out all unnecessary sound.

Nightmare Alley also had perhaps the most memorable final shot of any film last year – a close-up on Stanton, fully humbled and brought down to the filthy, stinking earth on which he’s spent the entire movie looking down. Cooper lets it absolutely rip in this shot.

In an ensemble packed to the gills with great performances, I’d like to single out Richard Jenkins as the low-key MVP. His Ezra Grindle is a frighteningly repulsive man, and yet Jenkins, with his inherent decency as an actor, somehow gets us to care when Stanton tricks Grindle and humiliates him. It’s one of many magic tricks Del Toro pulls off in Nightmare Alley, which has the audacity to eschew any platitudes about the triumph of the human spirit and acknowledge that, deep inside, a great deal of us are downright rotten to the core.

3. West Side Story (Steven Spielberg)

Nobody does it better than Steven Spielberg. I’ll admit I initially questioned the necessity of a remake of West Side Story, the spellbinding Broadway musical that was first adapted into a film in 1961 (winning ten Oscars, including Best Picture). But Spielberg (along with key collaborators, including screenwriter Tony Kushner and cinematographer Janusz Kaminski) makes this endeavor feel essential from the first frame to the last. This is a big, colorful and emotionally wrenching time at the movies.

On New York’s Upper West Side in the 1950s, two street gangs are engaged in a turf war – the Jets, comprised of second and third generation Irish and Italian Americans, and the Sharks, who are largely Puerto Rican. The two gangs are stand-ins for the Montagues and Capulets of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, and the star-crossed lovers from opposite sides who further escalate the gangland conflict are Tony (Ansel Elgort) and Maria (Rachel Zegler). After a chance encounter at a local dance, the two fresh-faced teenagers fall head over heels for one another – incensing both gangs in the process. Maria’s brother Bernardo (David Alvarez), the leader of the Sharks, meets with Riff (Mike Faist), the leader of the Jets, to discuss the terms of a “rumble” – a planned, violent confrontation between gangs that, as anyone who has read Romeo and Juliet knows, does not exactly set the course for Tony and Maria’s happily-ever-after.

The aforementioned “rumble,” which occurs about two-thirds of the way through West Side Story, is one of the most astounding and electric set pieces of Spielberg’s career. It doesn’t matter if you know the outcome. It is harrowing and tense, and one of the most memorable scenes in any movie last year.

This West Side Story is especially effective as an illustration of how two groups can be pitted against one another, each thinking the other is responsible for their disenfranchisement, while the real perpetrators (in this case, the City of New York clearing the neighborhood for what will become Lincoln Center) remain above the chaos. Spielberg and Kushner have made some fascinating changes to the source material in this regard. The presence of Puerto Ricans is not what’s causing the Jets’ disenfranchisement (that would be growing up without parents and role models, as articulated in the number Gee, Officer Krupke), but anti-immigration sentiment serves as an easy outlet for their rage and feelings of victimhood.

But these changes don’t feel like Spielberg and Kushner trying to make the story more “relevant” for a modern audience; instead, they’re taking thematic strands that have always been a part of this story’s text and fleshing them out in a way that resonate even more. After all, West Side Story was a musical that tackled nativism and class divisions long before those ideas were prevalent in mainstream musicals.

It’s a particular thrill to watch Spielberg wield his visual wizardry in a movie musical. Most of his contemporaries – Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Woody Allen, Robert Altman – have made big-screen musicals to varying degrees of success, but Spielberg’s sensibilities are perhaps the most in-tune with the showmanship needed to craft a memorable musical. West Side Story is another jewel to add to the director’s incredibly varied 21st century filmography, which has tackled startling visions of the future (Minority Report), reckonings with vengeance (Munich), whimsical comedy-drama (Catch Me If You Can, The Terminal), pure popcorn entertainment (The Adventures of Tintin, Ready Player One) and, perhaps most profoundly, detailed portraits of American history (Lincoln, Bridge of Spies, The Post).

4. Don’t Look Up (Adam McKay)

“We really did have everything, didn’t we?”

This is Adam McKay's best film. It'd be one thing if the entire movie felt like a lecture (I love Vice and The Big Short, but both films admittedly slip into this tendency) - but there is real emotional heft to this thing.

At first glance, it appears the entire film may be Leonardo DiCaprio and Jennifer Lawrence exhaustively warning the powers-that-be of an impending natural disaster. But then McKay turns it in an interesting direction – DiCaprio's character gets attracted to the limelight and is subsequently caught up in the media frenzy, leaving Lawrence on the sidelines as the pouty doomsday girl. One of the more emotionally affecting scenes in the film is straight out of Sidney Lumet's Network (1976) - DiCaprio's wife (Melanie Lynskey) confronts him in a hotel room about his infidelities with Megyn Kelly-lite (Cate Blanchett). And, just as William Holden does to Beatrice Straight in Lumet's film, DiCaprio brutally cuts ties with his devoted spouse in favor of a relationship with a more exciting and utterly vapid creature of television.

Even the characters who are on the side of science get distracted by the more entertaining news dominating the airwaves – the break-up of a music power couple, the President's illicit affair with her good ole boy Supreme Court appointee, the launch of a new smartphone. This is the world we've created.

Ultimately, Don't Look Up leaves us with an appropriately icky feeling. All of the exasperation, laughter, frustration and anger (both on our and the characters' parts) gives way to the inevitable – the ultimate silencer, in which all of the politicians, scientists, news pundits and comet-deniers meet the same indiscriminate fate (well, except for the shuttle that launches the President and other high-profile dignitaries into space before the impact). This final sequence – in which, yes, the world indeed ends – culminates in a moving dinner amongst the level-headed astrologists. While they choose to spend their final moments breaking bread with family, everyone else is panicking, the reality of the situation finally catching up to them. Of course, it's too late.

Here is a great example of a filmmaker getting maximum mileage out of his all-star ensemble. Too many films with packed casts invariably waste the talent involved – but here, every big name gets ample opportunity to showcase their range. In particular, DiCaprio is wonderful, working in a comedic mode of which we're thankfully getting to see more and more. Other standouts include Meryl Streep as the Trump-ian President and Mark Rylance as a socially inept tech billionaire (who seems to have trouble even being in the same room as other people).

On a side note, the critical reception of Don’t Look Up was ridiculously disheartening. Not since Alexander Payne's Downsizing (2017) has a go-for-broke film received such a muted, outright dismissive response from film critics, and it’s been particularly bizarre watching far less ambitious and interesting titles somehow pass the critical litmus test with flying colors.

5. The Tragedy of Macbeth (Joel Coen)

My nearly sold-out cinema burst into applause as soon as Joel Coen’s The Tragedy of Macbeth ended – which is notable considering that it was a crowd of folks who had gathered at 9:30pm on a Monday night to experience a black-and-white Shakespeare adaptation.

So, yes, this film is impeccably well-made. What's always astonishing about well-performed Shakespeare is how we understand the meaning of a scene not necessarily through total comprehension of every line, but through the feeling and delivery of the language. It really doesn't matter if you understand everything you hear – the dramatic purpose of a scene is always resoundingly clear and the internal struggles of the characters tangibly real.

With The Tragedy of Macbeth, Coen offers a nightmarish vision to accompany the text – the Bergman-esque imagery of his adaptation will stay with me for a long time. As always, the acting is superb. Marvel at the way minor Shakespeare characters are molded into colorful ancillary Coen creations (played by the likes of Stephen Root and Jefferson Mays). And where's the talk of Denzel Washington winning his third Oscar? It is a thrill seeing the actor tear into this role with all of his prowess. Give Washington free rein with the text of Shakespeare, August Wilson, Eugene O'Neill or Malcolm X and you'll get the finest acting on earth.

6. The French Dispatch (Wes Anderson)

Wes Anderson's The French Dispatch is the only movie I can recall that’s structured in the form of a literary magazine (complete with an opening obituary, an on-the-town briefing by a cycling Owen Wilson, and three feature stories from noted Dispatch journalists). Heck, there's even a cartoon section near the end of the film. Above all, this is a moving love letter to a ragtag team of expatriates who have found a home abroad in Ennui-sur-Blasé, France – far away from the magazine's base in Liberty, Kansas.

The most moving scene in the film involves Stephen Park’s Lt. Nescaffier, the personal chef to the Police Commissioner, musing aloud to journalist Roebuck Wright (Jeffrey Wright) about the reasons they both left their homelands to seek something else in France. The exchange was nearly cut out of Roebuck's piece, but French Dispatch editor Arthur Howitzer Jr. (Bill Murray) insists he include it. Not only is the scene the crux of Roebuck's article, it's also the emotional glue that holds the film together, bringing the thematic focus into clear sight.

As always with Anderson’s films, there’s an undercurrent of melancholy to every scene – a wistfulness buried beneath the staggering amount of visual information and gags packed into each frame (I always experience sensory overload when watching an Anderson film, never more so than with The French Dispatch). And the formal inventiveness never stops for a moment. One of my favorite bits is Roebuck’s journey through the labyrinth police station, in which he simultaneously addresses the audience and tries to figure out where the hell he is. The scene feels like a deconstruction of direct-address long-takes, in which a character leads us through a new world.

Another favorite: in the film's first story, titled The Concrete Masterpiece, writer J.K.L. Berensen (Tilda Swinton) stops midway through her lecture on the work of incarcerated artist Moses Rosenthaler (Benicio del Toro), crosses downstage and utters a series of revelations about Rosenthaler so disconcerting that it completely changes the tone of the scene. I’ll have to see the film again to pinpoint exactly what Anderson is doing here, but it caused an audible shift in my cinema audience.

All of the actors are wonderful here – particularly Wright and Murray, who share a scene late in the film that powerfully illustrates the protective home Howitzer Jr. has provided for his journalists.

7. The Last Duel (Ridley Scott)

Between The Last Duel and House of Gucci, Sir Ridley Scott truly outdid himself in 2021.

The Last Duel, in particular, races forward with narrative purpose. It’s an enormously entertaining portrait of contradictory perspectives, unreliable narrators and wounded machismo – dramatized on a characteristically enormous canvas by Scott. Matt Damon, Jodie Comer, Adam Driver and Ben Affleck are as excellent as you’d expect, and the script – by Damon, Affleck and Nicole Holofcener – inventively sidesteps every expectation of this kind of film.

In a just world, The Last Duel would have been one of the biggest hits of the fall. Go support good movies, people!

8. C’mon C’mon (Mike Mills)

Absolutely lovely. C’mon C’mon is the kind of film to get lost in, with its series of small moments resulting in a cumulative power that’s hard to shake after leaving the cinema. Mike Mills is three-for-three after Beginners (2011) and 20th Century Women (2016), and Joaquin Phoenix is utterly beguiling in one of his best and most natural performances. His character’s relationship with his nephew (a wonderful Woody Norman) is heartwarming in its sincerity.

A few scenes that touched me deeply: Norman asking Phoenix why he’s not married, and the way Phoenix responds by dipping in and out of the bedtime story he’s reading to his nephew, ultimately admitting he doesn’t know why his last relationship ended; Phoenix’s reaction upon learning his sister had an abortion; Norman’s immense sadness upon realizing he won’t remember most of his travels with his uncle by the time he gets older.

It’s true – I don’t remember many of the specifics of the times I spent with loved ones at a young age. But I remember exactly how they made me feel, and what they meant to me in that moment. That’s what carries on.

9. The Card Counter (Paul Schrader)

For William Tell (Oscar Isaac), there are two possible paths – one of salvation, and one of continued destruction.

The scenes between William and Cirk (Tye Sheridan) are among the best written exchanges of Paul Schrader’s career. There’s a constant dance happening between these two, as William considers following through with Cirk’s proposal to capture and torture Colonel Gordo (Willem Dafoe), the architect behind the atrocities committed against prisoners at Abu Ghraib. William has ample reason to choose this path – Gordo suffered no consequences for his actions, while William, who served under him, was sentenced to military prison. The temptation for vengeance is muted only by William’s impulse to take Cirk under his wing and guide him on the right path.

Schrader doesn’t victimize William in the slightest – yes, Gordo was the mastermind of the crimes at Abu Ghraib, but our hero unambiguously tortured prisoners. The question now is, does he continue down that path, or find some form of penance?

One thing I love about The Card Counter is that it’s not about poker in an abstract sense – the specifics of the high stakes card-playing world fill every scene. Most movies nowadays choose to simply indicate – as if the filmmaker were saying, “You won’t understand this complicated profession, so just trust us that our character is good at what he does.” But by giving us access to William’s inner life (largely through the character’s private journaling, which comfortably places The Card Counter among Schrader’s other man-in-a-room-writing-down-his-thoughts masterworks), the filmmaker allows us to understand exactly how this man does what he does, how he learned it, and how it informs his every move.

There’s a brilliant moment near the end of the film in which William plays opposite an overly patriotic poker player. I kept waiting for Schrader to show us William’s hand, but he doesn’t – instead, he simply lets the scene play out on the actors’ faces. At this point, we understand enough about William’s methods that we don’t even need to see the cards.

From the get-go, Robert Levon Been and Giancarlo Vulcano's score kept me in a heightened state of anxiety. Part of the pleasure of The Card Counter is having no idea where the film is going to go – while somehow also knowing exactly how things could go, and dreading that worst-case-scenario outcome for William.

On another formal note, I continue to find Alexander Dynan's cinematography for Schrader remarkably pleasing to the eye. Like First Reformed (2018), the camera movement and blocking of actors feels inspired by a Bresson movie from the 1950s, and yet the picture is unabashedly digital-looking, which for whatever reason makes every frame slightly unsettling (unlike First Reformed, which was 4:3, The Card Counter is a little bit wider at 1.66:1).

10. Last Night in Soho (Edgar Wright)

A second viewing really added to the experience on this one. The first time around, I was startled and disturbed by the film's excellent depiction of London's seedy underbelly, particularly in a mid-movie sequence that dips beneath the glamour of the dance floor and puts the full ugliness of this world on display.

I was less certain on first viewing exactly where director Edgar Wright was taking us, at least for the film's first half. Watching it again, I delighted in picking up on Wright’s masterfully-planted clues and got a certain kind of pleasure knowing exactly where this thing was heading. This allowed me to live in the world of the film a bit more – and what a world it is! The seediness aside, Last Night in Soho is an absolute blast of visual and musical delights. Wright has a ton of fun playing around with genre and the milieu of 1960s London. There were more than a few big, drab-looking movies released in cinemas last fall, but Last Night in Soho, in contrast, was full of life and color, not to mention genuine tension and menace.

I greatly admire Edgar Wright's work, but some of his films are almost a little too hip or self-reflexive for me (particularly Scott Pilgrim vs. the World – a movie I fully recognize is well-done, but most of the video game references are lost on me). But here, he's wrestling with larger ideas (romanticization of the past and mental illness among them) and dealing in pure genre territory (Last Night in Soho is fun, but it's not particularly funny – there are few comedic gags to be found). I guess what I'm saying is... this is my favorite Edgar Wright movie thus far, and it deserved to be a much bigger hit.

Special Jury Prize

Pretend It’s A City (Martin Scorsese)

This isn’t technically a film, but it’s too much of an absolute joy to not mention. In addition to being a delightful portrait of Fran Lebowitz and New York City, you can also play a fun game of Where’s Waldo with me in the audience, grinning like the exhilarated 22-year-old I was (specifically in Episode 6, Hall of Records). Does this count as being in a Martin Scorsese film?

I never knew if this footage would see the light of day – but here it is, put together beautifully. Watching Scorsese and Lebowitz peruse the New York Public Library makes one long for a buddy movie starring these two.

Can you find me?