This year’s top ten – heck, the entire top twenty-five – is incredibly strong. By the time I saw Clint Eastwood’s American

Sniper last week, I felt undeniably that it belonged in my top ten. And yet

the ten movies already there were so dear to my heart, that there simply wasn’t one I could take away. How something

as sublime as Wes Anderson's The Grand Budapest Hotel

could only be #10 on my list is still a mystery, which I suppose speaks to the strength of the movies on this list. As usual, the rankings are somewhat arbitrary, as any movie on this list could be justifiably called the best of the year.

Alejandro

González Inárritu’s Birdman is a tour-de-force of cinema. Michael Keaton gives the best

performance of the year as Riggan Thompson, a washed-up movie star most famous

for playing the superhero Birdman in a series of 1990s blockbusters. He’s now

writing, directing and starring in an adaptation of Raymond Carver’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love

on Broadway. In the process, he’s haunted by the voice of Birdman, who reminds

him at every turn that he doesn’t belong onstage – he belongs in a blockbuster.

Tumbling in and out of Riggan’s world are his daughter and now assistant, Sam

(Emma Stone), his manager Jake (Zach Galifianakis) and a critically acclaimed

stage actor (Edward Norton) intent on sabotaging the production.

The main visual conceit behind Birdman is that it’s meant to look like one long, unbroken take,

and on a purely technical level, the film has some of the most impressive

blocking of actors and camera choreography I’ve ever seen. I mean, the camera

is always in the right place at the right time. Never once does the

filmmaking feel locked-in. I never wanted Inárritu

to just cut and take us to another location. The sense of place is so well

established in Birdman – I’ve rarely

felt like I’ve experienced something in a certain location as vividly as I do with

the St. James Theater and the surrounding area in this movie.

Birdman also

understands and conveys the spontaneity of live theatre better than any movie I

can remember. Because performing onstage is one continuous experience, the

effect of the film unfolding as one take is incredibly effective, never more so than when Riggan and his fellow actors are in the

middle of a performance, where it truly feels like anything can happen. The movie has what I might call a “stragefright” element, something

I’ve been hoping to imbue in one of my own scripts - a free-wheeling,

downright musical quality (can we talk about Antonio Sanchez's kinetic drum score?) and tempo that perfectly accompanies its depiction of a man flustering his way through an

overwhelming mounting of a production.

And even when we’re watching scenes with characters that

aren’t Riggan, somehow the entire movie feels like an experience ripped from

his consciousness. The experiential aspect of this movie, to me, is even more

of an achievement than that of Alfonso Cuaron’s Gravity (2013), which similarly had numerous long takes (and also

was brilliantly filmed by cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezski). But the camera

choreography in Birdman mimics the chaos and unpredictability of everyday life, all the while capturing

every nuance and painful private moment of a fascinating group of characters

(the film co-stars Naomi Watts, Andrea Riseborough and Amy Ryan). The marks hit

in Gravity may have been technically

challenging and awe-inspiring, but rarely were they in the service of brilliant

dramatic storytelling as they are in Birdman.

It's hard to think of a better ensemble cast this year

(although Foxcatcher’s central three

actors are a close threat), with Norton, Stone and Watts all deserving of

nominations for their work. Keaton is on fire here, in a performance that lacks

any kind of vanity. He has always been one of the most relatable and natural actors, not

just in Batman (1989) and Beetlejuice

(1988), but in Jackie Brown (1997),

The Paper (1994) and The Other Guys (2010). He is this year’s

Best Actor.

Birdman is full of

incredibly bold and strong camera and performance choices, and every one of

them pays off. As Riggan races onstage in his underwear from the audience (after

getting locked out of the St. James Theater mid-performance, surely one of the

funniest sequences in a movie this year), Inárritu’s

camera moves backstage, past Jake hovering in the wings, and drifts to a

hallway and lingers there. Inárritu simply

lets the rest of the scene onstage play out off-screen, calling to mind a

similar shot in Martin Scorsese’s Taxi

Driver (1976). The shot of the hallway gives us a brief respite from the

franticness onstage, but it also seems to grant a kind of dignity to Riggan, shying

away from the stage in embarrassment, in horror at what he has to do to

finish his performance. It’s representative of every technical choice in the

movie working perfectly in tune with an emotional choice.

Earlier in the film, when Sam goes on a tirade against

Riggan for desperately wanting to stay relevant, there’s not a cut (or, in this

film, even a whip-pan) to Riggan’s hurt reaction after she spews vitriol at

him. The camera stays on her face, and it’s absolutely the most powerful choice

(and, man, does Emma Stone seize that moment). I can imagine how this movie

would be edited by a filmmaker without Inárritu’s

confidence and skill, but in his hands, every character in Birdman gets their own private moment of pain and suffering, and

the harmonious way in which it all clicks together is the work of a master.

In an interview with Rolling Stone, Inárritu explains the movie’s subtitle, The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance, as referring to “Riggan’s total

lack of experience in the theater world, how he goes into this for what may or

may not be the right reasons but, somehow, it helps him get to a place where he

can express himself better.” Beyond the film’s technical achievements and

stunning performances, the reason Birdman

resonates as much as it does is that the film doesn’t undermine Riggan’s

attempt to stage this ambitious vanity project; in fact, it celebrates his

risk. Throughout the film, Riggan is seemingly able to use his superhero “powers”

as Birdman to control various elements in his world – he can fly, he can make

objects move in his dressing room, he can send lights tumbling down onto

unsuspecting actors onstage – but we get the sense that it’s only in his own

mind, and nobody else suspects what he may or may not be capable of.

But, by the time we reach the wonderful final scene of the

film, Riggan has not rejected Birdman, but embraced him. And, for the first

time, someone else – specifically, his daughter – is able to see the powers

that previously only Riggan could see. His risk pays off, and someone else is

finally able to see him for who he truly is.

Richard

Linklater has made a version of all of the movies I could ever hope to make,

and more. He’s made the joyous backstage theatre drama (Me & Orson

Welles), the best romance in recent movie history (the Before Sunrise,

Before Sunset and Before Midnight trilogy), the story of the last

day of school at an Austin high school (Dazed and Confused) and a dark

comedy that explores the peculiarities of East Texas and its local flavor (Bernie).

With

Boyhood, his twelve-years-in-the-making

portrait of Mason (Ellar Coltrane) from age six to eighteen, Linklater has made

his best movie, a masterful epic that brings to mind Terrence Malick’s The

Tree of Life (2011), both in its ambition and in its Texas setting.

Roger Ebert wrote in his review of The Tree of Life that he didn’t “know

when a film has connected more immediately with [his] own personal experience.”

I suspect many people will feel this way about Boyhood, too.

Oh,

how this film will resonate for those who grew up in Texas. Linklater gets

everything right – the recitation of the Texas pledge in public schools, the

sound of white winged doves calling out over suburban neighborhoods, the Bible

given to you at a certain age with your name engraved on the cover.

Oh,

how this film will resonate for those who grew up in Texas. Linklater gets

everything right – the recitation of the Texas pledge in public schools, the

sound of white winged doves calling out over suburban neighborhoods, the Bible

given to you at a certain age with your name engraved on the cover.  Near

the end of the film, as she’s sending her son off to college, Mason’s mother,

Olivia (Patricia Arquette), says, “I just thought there’d be more, you know?”

And that’s when the power of the movie hit me.

Near

the end of the film, as she’s sending her son off to college, Mason’s mother,

Olivia (Patricia Arquette), says, “I just thought there’d be more, you know?”

And that’s when the power of the movie hit me.

Though

the movie has been lauded for its incredible twelve-year shoot, the greatest

achievement of Boyhood is that you don’t really notice the characters

(and actors) aging. The movie is so entertaining, the transitions so seamless,

and the characters such a genuine pleasure to hang out with, that you lose

sight of the fact that they’re growing up and maturing right before your eyes.

By not focusing on overly dramatic or seminal moments that other filmmakers

might make the focus of their coming-of-age films, Linklater gives the whole

movie such a hang-out feeling that the trick is not thinking about the time.

And I thought there’d be more. But that’s how it happens. It’s all over too

soon, and perhaps the power of the movie doesn’t even fully register until you

realize it’s all over.

In

the first half of this film, Mason is pulled in many different directions, with

adults offering out various ways through life. It’s not until about midway

through Boyhood that Mason really emerges and develops a voice. That’s

not an arc we see much in cinema, particularly with so much emphasis placed on

active characters. But how are we formed? Aren’t we all slowly molded by the

world around us? Much of our childhood is spent not thinking about the future

and not making active decisions. We’re certainly not thinking about what we’re

doing as part of some larger life structure.

Each of Mason's failed or potential father figures in the movie remain in my mind. I think of the sadness of Mason's second stepfather, who is a good man and a war veteran. But because of Mason's experience with his alcoholic, abusive first stepfather, he disregards his second stepfather's advice. There's absolutely no judgment here by Linklater. I've read articles that refer to Mason's stepfathers as a series of deadbeats, which is an absolutely incorrect assessment when referring to his second one, just as it's entirely incorrect to dismiss the gun culture of Mason's stepmother's West Texas parents as ridiculous. It's more about where Mason is in his adolescence than the rightness or wrongness of any of these potential guiding figures. It's about paths - the ones laid out before you, the ones you choose, even when you don't feel yourself making a discernible choice.

Each of Mason's failed or potential father figures in the movie remain in my mind. I think of the sadness of Mason's second stepfather, who is a good man and a war veteran. But because of Mason's experience with his alcoholic, abusive first stepfather, he disregards his second stepfather's advice. There's absolutely no judgment here by Linklater. I've read articles that refer to Mason's stepfathers as a series of deadbeats, which is an absolutely incorrect assessment when referring to his second one, just as it's entirely incorrect to dismiss the gun culture of Mason's stepmother's West Texas parents as ridiculous. It's more about where Mason is in his adolescence than the rightness or wrongness of any of these potential guiding figures. It's about paths - the ones laid out before you, the ones you choose, even when you don't feel yourself making a discernible choice.

Many

of the major character changes take place off-screen. The movie is not unlike

Kenneth Lonergan’s Margaret (2011) in this respect, where characters are

allowed to leave a scene and have lives outside the movie. I think of Mason’s

father, Mason Sr. (Ethan Hawke) growing from freewheeling dad in one section of

the movie to a slightly more conservative and mature man entering his second

marriage a bit later. We see how this change must have taken place. To witness

the change itself is not necessary.

The

actors in Boyhood are extraordinary, and you’d be hard-pressed to

argue that any other film performances this year are really comparable to what

Arquette, Coltrane, Hawke and Lorelei Linklater achieve in this movie. In

particular, I’d like to see Hawke at the very least get nominated for an

Academy Award for his performance – he’s an absolutely fantastic actor,

extraordinary in everything from Linklater’s films to Sidney Lumet’s Before

the Devil Knows You’re Dead (2007) to Training Day (2001).

As

Linklater says in an interview, “At some point, you’re no longer growing up,

you’re aging. But no one can pinpoint that moment exactly.” I can’t wait to see

Boyhood again to see if I can pinpoint exactly where it happens, but I

have a feeling I’ll be taken away on Mason’s journey once again and forget

about that question altogether, enjoying my time with wonderfully real people.

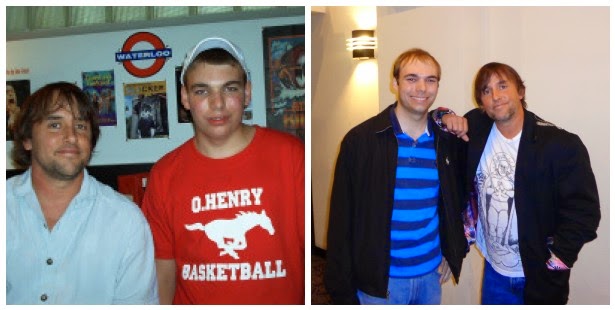

I’ve

had my own boyhood with Mr. Linklater (see the pictures to the left). I don’t

mean to say he has any idea who I am, but by growing up in Austin and being

interested in film, I (along with many others) feel a certain kinship with him.

He

is our resident auteur, and more. He’s the friendly patron of the arts, the man

sitting behind me at Hyde Park Theatre’s production of Killer Joe. He's

the guy enthusiastically talking with cinephiles in between the Summer Classic

Film Series screenings of Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull (1980) and Goodfellas (1990)

at the Paramount Theatre. He came to Waterloo Video to sign the newly released

Criterion DVD of Slacker back in 2004, and I have my

copy proudly placed atop my DVD collection. “To Jack – all the best. Rick

Linklater.”

I’ve

never been more proud to come from the city of Linklater. The Texas auteurs –

Linklater, Terrence Malick, Wes Anderson, David Gordon Green – are responsible

for many of the best films of the last few years (including two more movies on this list, The Grand Budapest Hotel and Joe). I can only hope that in a few months, we’ll be referring to Linklater as an Academy Award-winning director.

Special

Note: In one of the scenes filmed at Austin High School, you can see the 2009

UIL One-Act Play State Champions banner hanging over the Preas Theater (for our

production of Over the River and Through the Woods, in which I was one

of the six actors). We didn’t just win State – we made it into a Linklater

movie!

The strange, horrifying true story dramatized in Bennett

Miller’s Foxcatcher begins and ends

with billionaire John du Pont (Steve Carell) desperately wanting to fit in.

As the film opens, du Pont calls on Olympic Wrestling champion Mark Schultz

(Channing Tatum) and offers his Foxcatcher Farms estate as the training ground

for the 1988 Olympics wrestling team.

Du Pont has never known real friendship or love, and

Carell brilliantly plays him as a man who desperately wants both, but doesn’t

have the slightest clue as to how to attain them. The scenes of du Pont

watching the brotherly love between Mark and his

charismatic brother and fellow Olympic Wrestling champion Dave Schultz (Mark

Ruffalo), and trying to imitate that, are heartbreaking.

There are so many tremendous, funny and tragic sequences

in Foxcatcher, not the least of which

involve the bond formed between du Pont and Schultz. At one point, the wrestlers, while training at Foxcatcher,

cheer du Pont on when they see him at the shooting range firing a gun with

local law enforcement. Taking this as a possible sign of respect, du Pont later

brings the gun into the gym and fires a bullet into the ceiling – not to scare

anyone, really, but just in a desperate bid to have the guys like him. When he

later tries to bond with his wrestling team after a victory by getting drunk

and railing against his mother (Vanessa Redgrave), it's terribly sad. As the picture goes on, the bond between du Pont and Mark gets stronger and stranger. In a wonderfully bizarre sequence set to This Land Is Your Land as performed by Bob Dylan, they even give each other haircuts.

And yet there is something about Mark that makes his bond with

du Pont very real and striking and weirdly moving – they both seem very lost

and alone, and find in each other a kind of companionship, at least until du Punt goes too

far and humiliates Mark in front of his wrestling team. From there forward, it becomes Dave Schultz that du Pont courts.

The friendship between du Pont and Mark that sustains its

way through the first half of the movie remains a bit of a haunting mystery,

even after three viewings of the movie. What did they see in each other? Was

there a moment where either one of them felt they had found a friend, however

strange the circumstances were?

I cannot emphasize how strong the three central

performances in this movie are – Carell, Tatum and Ruffalo give the best performances of their careers. Tatum performing with his posture alone is incredible.

There are shots of him from behind where he expresses more with his back than

many actors can with their face. He plays Mark as a hulking, semi-inarticulate

brute, living in his brother's shadow.

But when Mark goes on a self-destructive eating binge

after losing a key match, it's only Dave who can train him back to make the weight maximum. And the scene that

follows – as Mark trains and Dave refuses to let du Pont into their world –

is crushing for du Pont, precisely because he can't seem to be a part of it.

Dave almost helplessly watches as this strange encounter between his brother and du Pont falls apart, and his genuine attempt to make things better for both of them leads to the film’s tragic conclusion. It’s almost as if Dave, who is the only one of our central three who has found a way to a normal life, has to be brought down to the misery of the other two men. Ruffalo is heartbreakingly great in this role.

I came out of Foxcatcher

feeling for all three men – even du Pont, whose loneliness must have been crippling,

and a figure as charismatic and seemingly happy as Dave Schultz must have seemed

frustratingly out-of-reach. Foxcatcher

works so beautifully because Miller, through mainly subtext and looks among these

three deeply different characters, makes the tragedy seems inevitable given who

these people are. He makes us feel the Shakespearean weight of this story through

subtext and small glances, and an inarticulable sadness that no amount of wrestling or

brief friendships can relieve. With Foxcatcher, Capote (2005) and Moneyball (2011), Miller has given us three of the great American films of the past decade.

There’s no one viewing of Paul Thomas Anderson’s masterful

adaptation of Thomas Pynchon’s novel Inherent

Vice. This is one, like Anderson’s The

Master (2012), where you go back and discover more. After their collaboration on The Master two years ago, Anderson and star Joaquin Phoenix have outdone themselves here.

Doc Sportello (Phoenix) is a consistently-stoned private detective in early 1970s Los Angeles trying to make sense of an ever-evolving murder-kidnapping scheme brought to him by his ex-girlfriend Shasta (Katherine Waterston).

Doc Sportello (Phoenix) is a consistently-stoned private detective in early 1970s Los Angeles trying to make sense of an ever-evolving murder-kidnapping scheme brought to him by his ex-girlfriend Shasta (Katherine Waterston).

The party of the 1960s has ended when the movie starts. Doc is

always on the verge of discovering something – he has a vague awareness of the

larger, sinister forces that are corrupting Los Angeles – but it never quite

coheres. But even when it looks like he isn’t quite up to the task of

connecting the dots and bringing anyone to justice, sometimes Doc has moments when

he understands things quite well, I think. These moments, though, are fleeting, like brief flashes of lucidity

before crawling back into a melancholy hole of 1960s nostalgia. Even the chief

missing person, Mickey Wolfmann (Eric Roberts), is so drugged out of his mind

that he doesn’t seem to have a clue as to what’s going on.

The closest thing anyone has to resolution, really, is the

return of saxophonist Coy Harlingen (Owen Wilson) to his family from the grips

of a strange cult, which is really the most anyone can hope for in this world.

Both times I’ve seen the film, Inherent Vice strikes me as being at least partially about the

friendship between Doc and hippie-hating Los Angeles Lieutenant

Detective Christian F. “Bigfoot” Bjornsen (Josh Brolin), who both have been

sort of rendered useless and irrelevant in their time. They both seek

other careers – Bigfoot as an actor, Doc as a doctor. Bigfoot is an oaf who

can’t get any respect within his own department and with his own seemingly

conservative values, and the clues Doc writes down on his notepad are rarely

solved.

Both times I’ve seen the film, Inherent Vice strikes me as being at least partially about the

friendship between Doc and hippie-hating Los Angeles Lieutenant

Detective Christian F. “Bigfoot” Bjornsen (Josh Brolin), who both have been

sort of rendered useless and irrelevant in their time. They both seek

other careers – Bigfoot as an actor, Doc as a doctor. Bigfoot is an oaf who

can’t get any respect within his own department and with his own seemingly

conservative values, and the clues Doc writes down on his notepad are rarely

solved. By the end of the movie, Bigfoot and Doc seem to bond mainly because they both seem lost, adrift in the changing of the times and their inability to really lay down the law.

Martin Short, as Dr. Rudy Blatnoyd, is a hysterical

highlight, and his scenes give the movie a wild and frenetic energy that is

perfectly matched by the more melancholic feeling the rest of the movie

provides. We get brief glimpses at the “grooviness” of the old world, and it’s ridiculously entertaining. With Inherent Vice, many people may expect a film that captures that "grooviness" for two-and-a-half hours straight,

in the same vein as Anderson’s breakout masterpiece Boogie Nights (1997). But Anderson and Pynchon are more interested

in the afterglow, the feeling of the hangover that follows the party. When the

movie erupts in joyous moments of energy (such as when Anderson lovingly cranks

up Les Fleurs by Minnie Riperton), we’re suddenly energized by the comic

absurdity of it all. But for the most part, the movie is fused by a spirit that’s unlike any movie I’ve ever seen.

Not that Inherent Vice

isn’t absurdly funny even in its more melancholic scenes – in fact, it’s

probably the most I’ve laughed in a cinema this year (it’s funny that the best

comedies now come in the form of auteurs going for broke, with Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street easily being the

funniest movie of last year).

Though comparisons have been made to Joel and Ethan Coen’s The Big Lebowski (1998), these are very different films, in

that Lebowski revels in the lifestyle

and philosophy of The Dude. I think Anderson is onto something a little darker

here. The actual plot doesn’t seem to matter much in either film, but

in Inherent Vice, Anderson doesn’t

play for as much comedy with his stoned protagonist not understanding or trying

to make sense of the narrative.

Though comparisons have been made to Joel and Ethan Coen’s The Big Lebowski (1998), these are very different films, in

that Lebowski revels in the lifestyle

and philosophy of The Dude. I think Anderson is onto something a little darker

here. The actual plot doesn’t seem to matter much in either film, but

in Inherent Vice, Anderson doesn’t

play for as much comedy with his stoned protagonist not understanding or trying

to make sense of the narrative.

The flashback sequence to a happier time – with Neil Young’s

Journey Through the Past playing over

Doc and Shasta running in the rain and falling into each other’s arms on a block in Los Angeles – is representative of the film’s wistful tone in general. That scene is immediately followed by

Doc’s strange present-day return to the same block, where an empty lot has now been

replaced by a dental facility in the shape of a tooth (land

development and the changing landscape of Los Angeles neighborhoods also play a

large role in the movie, not unlike in the great Los Angeles noir Chinatown).

The movie feels like a nightmare, with Doc operating in a world that no longer makes sense, facing an unsettling sensation of forces beyond his control. I haven’t read Thomas Pynchon’s novel, but a close friend

tells me this is one of the most faithful adaptations from book to screen he’s ever seen.

Not only that, but the movie actually unearths some of the key themes buried in

the book’s dense language. There’s no question that Inherent Vice leaves you with a very specific and unnerving

feeling, and for Anderson to go within the book and access not only the

complexity of the plot, but also to bring out the feeling in it, makes this

film an incredible achievement. The last scene will stay with you for days, and

though you may not know what, exactly, to make of it, there’s no question about

how it makes you feel.

Early in the fall, I was lucky enough to nab a last-minute

ticket to the World Premiere of David Fincher’s Gone Girl at the New York Film Festival. From the first frame to

the last, this movie is absolutely brilliant and horrifying. I haven’t seen a

movie that plays so well on our fears of the media ripping us to shreds.

Gillian Flynn, adapting her own novel, wrote one of the

year’s best screenplays. The film concerns Nick Dunne (Ben Affleck), who is

suspected of having murdered his wife Amy (Rosamund Pike) after she disappears

from their Missouri home, and the media circus that ensues surrounding her

disappearance. Fincher taps into a very scary reality, in which one lives the rest of their lives in fear of the media and public perception.

If you haven’t seen the film or read the book, you may want

to stop reading here. With Amy, Gone Girl

gives us a kind of female character rarely depicted onscreen – a cutthroat

woman aware of the cards stacked against her and willing to destroy the lives

of those around her to escape her marriage.

Actually, the film gives us many different kinds of strong

female characters. There’s diabolical Amy, yes. But there’s also Margo (Carrie

Coon), Nick’s twin sister and confidante, who wants to believe Nick is innocent,

but even she has her suspicions. My favorite character is perhaps Detective Rhonda

Boney (Kim Dickens), whose seeming no-nonsense attitude actually masks a pretty

admirable belief in innocent until proven guilty. She’s one of the few people

who actually still believes in the truth – not even her male counterpart,

Office James Gilpin (Patrick Fugit), is willing to give Nick the benefit of the

doubt, instead taking the media’s instant-blame bait.

Left on the sidelines are those who refuse to play the media-circus

game, like Tommy O’Hara (Scoot McNairy), who long ago resigned against Amy’s

efforts and has paid the price of being a leper. Gone Girl argues that you have to be a cutthroat piece of crap to

survive the circus. If Nick didn’t ultimately stoop to Amy’s level in the final

third of Gone Girl and cater to the

bait that the media wants, he would have spent the rest of his life in prison. In

the end of Gone Girl, Nick and Amy

more or less deserve each other, though the gender divide between who is to blame

for this twisted marriage may make this the worst date movie ever.

This movie is a horror show, and nobody – particularly the

media – is left unscathed. Gone Girl

is disturbingly hilarious, and rather than hide behind politically-correct

generic notions of gender, Fincher and Flynn actually address the differences in the ways in which men and women can play

on each other’s deepest fears. I think that’s why the movie strikes such a

nerve and leaves you so unsettled.

The movie is prescient in so many ways, particularly in the way it lampoons (or, sadly, merely depicts) the way we respond to these kinds

of news stories. Fincher, who has

become the master of the procedural with his masterpieces Zodiac (2007) and The Social

Network (2010), scorches us again. He is perhaps the only big-budget filmmaker willing to show us the ugliness of the world in which we live.

The

quiet of outer space is astonishing in Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar. Taking a cue from the majestic silence of Stanley

Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey

(1968), it was a joy to sit in the cinema and experience the vastness of the

surrounding

planets, wormholes and galaxies Nolan puts onscreen, hearing only the beautiful

sound of the film projector running.

This

is a positively gigantic movie. It’s Nolan’s most ambitious film to date,

tackling huge themes and intercutting between stories set in outer space and on

Earth. How many films consider whether we’re ruled by emotion or logic – and

which benefits our survival? Interstellar

is also Nolan’s most life-affirming and emotional movie to date, trading in the

darkness of Inception (2010) and The Dark Knight (2008) for a tale of

resilience.

The

Earth is dying, and while most of the human race is scrambling to plant new

crops and farm their way to survival on this planet, former pilot and engineer

Cooper (Matthew McConaughey) is not content to wither away on Earth and watch

his children die from the dust. He and his daughter, Murph, both adventurers

and explorers in spirit, stumble upon the remaining scientists and physicists

who comprise NASA, none of whom have Cooper’s experience and training as a

pilot. With no hope for Earth’s future in sight, Professor Brand (Michael

Caine) asks Cooper to pilot a mission into outer space to find an inhabitable

planet for the human race.

Nolan’s

dense, layered dialogue has developed with each one of his films into its own

kind of language, with its own unique rhythms. These are unmistakably characters

talking in a Christopher Nolan movie, and I mean that in the most complimentary

way possible. Hearing McConaughey deliver these lines is immensely satisfying –

I can’t think of a better actor to ground a film of this scope and magnitude.

McConaughey himself is a bit larger-than-life, and we believe him for every

second as he embodies the pioneering spirit that created America’s great space

program. Just as Leonardo DiCaprio was the perfect actor to bring emotional

weight and believability to the complex world of dreams in Inception, McConaughey is terrific here as the sincere pioneer who

can save the world.

Nolan

is one of the best emotional directors working, by which I mean that even when

questions arise about how things work

or what’s going on in the movie (even

with characters providing a necessary amount of explanation, you’ll still have

questions), Nolan is always there to guide us emotionally. But like Inception, which had a similarly heady

plot, Interstellar is meant to be

felt and experienced more than understood. And nobody can get you caught up in

a film’s momentum, excitement and emotional power better than Nolan. This is

exactly the kind of non-ironic, large-canvas epic that used to soar – closer in

feeling to the Hollywood pictures from the 1980s, with the spirit of The Right Stuff (1983) and many of the

best Steven Spielberg movies.

And

the film doesn’t stop there. Even during its resolution, Cooper keeps going –

he’s only interested in moving forward, pioneering the next wave. With each

film, Nolan keeps doing the same thing.

See

Interstellar in glorious 35mm or 70mm

film rather than digital projection, as Nolan would prefer. It’s far too rare

these days that any thought or care is taken as to how a movie is projected in

a cinema, and it’s gratifying to see Paul Thomas Anderson, with The Master, and now Nolan, with Interstellar, shoot their film a

specific way and insist that many theaters show it that way.

I

often walk out of movies and struggle to articulate the effect they have on me.

Roger Ebert was a master at this. He always had a perfect turn of phrase to

capture exactly what a certain movie felt like. Who else could write something

like, “I was almost hugging myself while I watched it” of Cameron Crowe’s Almost

Famous (2000)? I think of that quote every time I watch Almost Famous,

because that’s exactly how the movie makes you feel.

On

the opening night of Steve James’s new documentary about Ebert, Life Itself,

I was moved to tears, just as I had been the first time I saw the movie in

January. Walking out of Austin’s Violet Crown Cinema and seeing the peaceful

Austin skyline before me, a banner poster of Boyhood proudly draped over

the cinema, I was touched by a tinge of sadness.

Partially

because this journey isn’t yet over. Many of us left have yet to enjoy our

heyday. Some of us never get there. Roger Ebert did, and the morning after he

passes away in Life Itself, Steve James shows us a Chicago infused with

sunlight and purpose. Forty years ago, there was Ebert, part of the very fabric

of that city, informing the lives of its people. And now, he’s gone.

This

is to say I don’t know how to articulate exactly how I felt looking out at the

city skyline after this movie ended. Certainly, I was overcome with sadness,

knowing that Ebert is gone and not coming back. But I was also filled with joy,

knowing that a city – in his case, Chicago – could contain a man such as this,

who stood for the right things and whose writing guided so many people to see

pictures they may never have seen otherwise.

The

film’s score plays an integral role in this magnificent feeling. The music by

Joshua Abrams hits a feeling somewhere between triumphant and mournful. There’s

something truly grand about it – as soon as you hear it, it just feels right.

It’s the score a life like this deserves. With the aid of that score, those

final shots of trains running through Chicago the morning after Ebert’s death

give the movie an almost transcendental power. This movie embodies such a

specific feeling and attitude toward a man, his life and the city in which he

lived.

Watching

Life Itself, I understood, in a way, what people mean when they say

death is a beautiful thing. The movie’s celebration of life and reconciliation

with death took me aback. When I saw the film for the first time in January, I

was focused on how well the movie illustrates Mr. Ebert’s impact on cinema and

his relationships with many of the filmmakers he championed. But I may have

missed the fearless quality of the movie to look at something deeper, going

into the unknown and ultimately coming to peace with Ebert’s passing. I felt

Ebert’s bravery more this time.

I’ve

not seen a movie that treats death with such forthrightness since Sean Penn’s Into

the Wild (2007), at least in the sense that death is accepted in both films

and shown for what it is.

During

one section of the movie, Ebert’s friend Bill Nack recites the last page of

Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby by heart, and perhaps that’s as good a way

as any to reconcile this thing that happens to all of us in the end. Life

Itself is one of the best films I’ve seen, not simply because it captures

what made Ebert so important and influential to the film community, but because

it’s one of the few movies that’s left me with a profound impression about what

it means to face death.

So,

reflecting after the movie, I thought about this ether space – the space

between the old world, where Ebert was alive and influenced how I thought of

cinema, and this new world, where recent movies seem almost out-of-balance

without his writing and guiding them to their proper alignment. As Ebert goes,

so does a whole way of living, a whole time and place for me. He is more

than a part of my childhood. He is sort of the leader, along with Martin

Scorsese, of everything I hold sacred and thrilling in movies.

And

here was this new city in front of me, full of life and those who may never

know what kind of man was here for a time and informed the way we feel and

react.

Few movies pulse with the life and force of Damien Chazelle's Whiplash, which, like Birdman, is set to constant drum beats

and never stops moving forward with purpose and energy. It's cut exactly how a movie should be cut - it's a small-budget independent movie, yes, but it doesn’t have any of the handheld naturalism that seems almost required of indies nowadays. Birdman and Whiplash move at the tempo of real life, and both seem so alive that anything could happen at any moment.

Rarely have I felt a knot in my stomach that comes from a movie so correctly and viscerally showing me how it feels to sit in a big city classroom full of artists. Andrew (Miles Teller) is a drummer at one of the top music conservatories in the country, and he's willing to do anything to please his demanding instructor Fletcher (J.K. Simmons). The movie tackles the relentlessness with which one can pursue anything to be included in the pantheon of greats.

Yes, it’s about bleeding for your art, like Darren

Aronofsky’s Black Swan (2010), but at

a certain point in the film, it’s also about having to face the fact that

you’re never going to be the best at doing what you love. And then, even once you've faced that realization, how quickly that can turn around in an instant. There's that thought that always lingers in the back of Andrew's head, No, but in the end, I

really will make it, and I will become the world's greatest drummer.

Yes, it’s about bleeding for your art, like Darren

Aronofsky’s Black Swan (2010), but at

a certain point in the film, it’s also about having to face the fact that

you’re never going to be the best at doing what you love. And then, even once you've faced that realization, how quickly that can turn around in an instant. There's that thought that always lingers in the back of Andrew's head, No, but in the end, I

really will make it, and I will become the world's greatest drummer.

Andrew has to have all or nothing. When he gets

expelled from the conservatory, he shoves away everything related to music. A comparison might be if I had to go see movies knowing I had somehow been banished from the film industry. You can’t be around

the things that make you feel that way. You have to resign to the fact that

you can’t be a part of it, and then remove it from your life entirely. Andrew reaches out to his ex-girlfriend, with whom he broke up so that he could concentrate on his craft, but she has a boyfriend. He's alienated everybody.

When Fletcher seems to give Andrew another opportunity - only to sabotage him in front of an audience - Andrew decides to play his own music anyway. With his ferocious musicality, it's as if he says, I can only survive onstage. My family isn't enough, my girlfriend has moved on, and this is the only way I can express myself - so you're going to let me play my drums! The energy is furious. The ending is a whirling, dazzling display – like a furious opera that expresses the anger and powerlessness that Andrew and Fletcher cannot.

When Fletcher seems to give Andrew another opportunity - only to sabotage him in front of an audience - Andrew decides to play his own music anyway. With his ferocious musicality, it's as if he says, I can only survive onstage. My family isn't enough, my girlfriend has moved on, and this is the only way I can express myself - so you're going to let me play my drums! The energy is furious. The ending is a whirling, dazzling display – like a furious opera that expresses the anger and powerlessness that Andrew and Fletcher cannot.

Whiplash so easily could have been a movie that simply asks, where do you draw the line between artistic obsession and taking it too far? But Chazelle knows it's more complicated than that. Fletcher and Andrew match each other in their intensity and near insanity, and the ending is almost joyous in the sense that they’ve found in

each other a kind of soul mate.

Andrew's father, Jim (Paul Reiser), gets a glimpse at the madness from the side of the stage, and he's essentially shut out of the equation. Andrew tried living a different life, a life without music, but he can't go back to that. It was empty. He doesn’t belong anywhere else – this is it for him. He only belongs onstage.

Andrew's father, Jim (Paul Reiser), gets a glimpse at the madness from the side of the stage, and he's essentially shut out of the equation. Andrew tried living a different life, a life without music, but he can't go back to that. It was empty. He doesn’t belong anywhere else – this is it for him. He only belongs onstage.

The

first thing that struck me about James Gray’s The Immigrant, which I saw

at last year’s New York Film Festival, were the faces of the actors in the

film - so many haunted, gaunt and pale faces. People looked different in 1920s

New York than they do today, and this is one of many important details that

lend a great authenticity to this movie. One of the most beautiful-looking

films I've seen in some time (photographed by Darius Khondji), the burlesque

houses, crowded tenement buildings and spectacular magic shows for Ellis Island

immigrants deeply rooted me in a time and place unlike anything I’ve seen

since Martin Scorsese’s Gangs of New York (2002).

Gray,

one of my favorite filmmakers, participated in a Q&A with the audience

after the screening. The film is full of breathtaking, sweeping images of 1920s

New York, and yet, like all of Gray's work, this is a very intimate movie. I

asked Mr. Gray if, when writing the film, he was thinking about the number of

large set pieces compared to the more intimate scenes with only a few actors.

Gray answered that The Immigrant is the kind of film United Artists

might have released back in 1978, but these days, it is, of course, very

difficult to secure funding for a large-scale, dramatic period piece of this nature.

So, yes, he did write thinking about the number of expansive scenes versus the

intimate ones, and tried to include many of the larger set-pieces in the

opening of the movie, allowing the picture to slowly grow more intimate.

Ewa

is referred to early on in the film as a ‘woman of low morals,’ as her behavior

and promiscuity on the boat to America are called into question. Throughout the

film, we watch as Ewa battles with her own sense of morality and what she feels

she deserves. She tests her morality by continually engaging in behavior she

feels certain will send her to hell, but in order to survive in America, she

has no other choice. Late in the film, Ewa asks her aunt, “Is it a sin to want

to be happy when you know you’ve done so many things wrong?” I felt myself

growing an extreme distaste for Bruno, who subjects Ewa to so many awful

experiences.

But

in the same way that the characters in Robert Altman's Nashville (1975) defy

our expectations of who will rise to the occasion*, so, perhaps, does The

Immigrant subvert our expectations of Bruno. Though both the audience and

Ewa may initially revile Bruno, my heart ultimately broke for him by the end of

the picture, because he is, I believe, a good man. He is truly and hopelessly

in love with Ewa and is trying, in his own flawed way, to earn her love. The

jealously, longing and fury in Phoenix’s performance is breathtaking; this is a

great companion piece to his extraordinary performance in Gray’s masterpiece Two

Lovers (2009).

Jeremy

Renner, as Orlando the Magician, enters midway through the movie and changes

the dynamic entirely. Imbued with a bit of magical realism, his character shows

Ewa that there’s something beyond the dreary life of prostitution. Again,

though, our expectations are challenged and a harder truth sets in – while the

dashing and charming Orlando appears to have all of the answers and offers Ewa

a way out of this life, does he really love Ewa like Bruno loves her? And,

ultimately, is he really looking out for Ewa any more than Bruno?

Jeremy

Renner, as Orlando the Magician, enters midway through the movie and changes

the dynamic entirely. Imbued with a bit of magical realism, his character shows

Ewa that there’s something beyond the dreary life of prostitution. Again,

though, our expectations are challenged and a harder truth sets in – while the

dashing and charming Orlando appears to have all of the answers and offers Ewa

a way out of this life, does he really love Ewa like Bruno loves her? And,

ultimately, is he really looking out for Ewa any more than Bruno?  There

are not easy answers to these questions, and as the film goes on, the

relationship between Ewa and Bruno grows more and more complex. Is Bruno taking

advantage of her, or is he offering the best version of the American Dream of

which he knows? Talking about the movie after the screening, Gray described the

relationship between Bruno and Ewa as strangely “co-dependent." In the

final scene of the movie, there is a forgiveness and understanding between

these two that moved me deeply. The beautiful and haunting last shot of the

film illustrates their separation and their connectedness.

There

are not easy answers to these questions, and as the film goes on, the

relationship between Ewa and Bruno grows more and more complex. Is Bruno taking

advantage of her, or is he offering the best version of the American Dream of

which he knows? Talking about the movie after the screening, Gray described the

relationship between Bruno and Ewa as strangely “co-dependent." In the

final scene of the movie, there is a forgiveness and understanding between

these two that moved me deeply. The beautiful and haunting last shot of the

film illustrates their separation and their connectedness.

I

came away from The Immigrant feeling so much for both of these

characters. Joaquin Phoenix's Bruno belongs on a list with other recent

characters in cinema who, for whatever reason, stay with me and earn such an

unexpected amount of empathy (I think of Greta Gerwig in Frances Ha,

and, further back, Ryan Gosling in Blue Valentine). After the screening,

I told Mr. Gray that I think his work is incredible - between The Immigrant and

Two Lovers, he has made two of the finest movies of the last decade.

*(In

her review of Nashville, Pauline Kael wrote, ‘Who watching the pious

Haven Hamilton sing the evangelical ‘Keep a’ Goin,’ his eyes flashing with a

paranoid gleam as he keeps the audience under surveillance, would guess that

the song represented his true spirit, and that

when injured he would think of the audience before himself?’)

At one point, I didn’t think there would be a richer film in

2014 than Wes Anderson’s The Grand

Budapest Hotel. And in many ways, there wasn’t. Second by second, I don’t

think there’s another title on this list that gave me such joy and haunted me as much as this film.

This is the first Wes Anderson picture during which I can remember experiencing real fear and dread - particularly during the chase sequence in which the henchman Jopling (Willem Dafoe) follows well-mannered Deputy Kovacs (Jeff Goldblum) into a museum. I sat there thinking, well, Jopling isn't going to kill Kovacs. But when he does, it's horrifying, because the film and its sensibilities are as refined and dignified as the great M. Gustave (Ralph Fiennes) himself. And slowly, throughout the movie, this other world starts creeping in - best represented by the crude and villainous Dmitri (Adrien Brody) and his family.

The civilized but fragile world - lovingly created by Anderson's brilliant eye, filled with romance and wonder - crumbles, and by the end of the movie, it's only but a memory of a memory. Thirteen years ago, Anderson's The Royal Tenenbaums (2001) was my favorite movie of the year. The Grand Budapest Hotel may be his best film since Tenenbaums, and in any other year would have placed much higher on this list.

This is the first Wes Anderson picture during which I can remember experiencing real fear and dread - particularly during the chase sequence in which the henchman Jopling (Willem Dafoe) follows well-mannered Deputy Kovacs (Jeff Goldblum) into a museum. I sat there thinking, well, Jopling isn't going to kill Kovacs. But when he does, it's horrifying, because the film and its sensibilities are as refined and dignified as the great M. Gustave (Ralph Fiennes) himself. And slowly, throughout the movie, this other world starts creeping in - best represented by the crude and villainous Dmitri (Adrien Brody) and his family.

The civilized but fragile world - lovingly created by Anderson's brilliant eye, filled with romance and wonder - crumbles, and by the end of the movie, it's only but a memory of a memory. Thirteen years ago, Anderson's The Royal Tenenbaums (2001) was my favorite movie of the year. The Grand Budapest Hotel may be his best film since Tenenbaums, and in any other year would have placed much higher on this list.

The Rest of the Best:

11. American Sniper (Clint Eastwood)

12. A Most Wanted Man (Anton Corbijn)

13. Nightcrawler (Dan Gilroy)

14. The Homesman (Tommy Lee Jones)

15. Under the Skin (Jonathan Glazer)

16. Noah (Darren Aronofsky) *full review coming soon

17. Wild (Jean-Marc Vallee)

18. Calvary (John Michael McDonagh)

19. The 50 Year Argument (Martin Scorsese and David Tedeschi)

11. American Sniper (Clint Eastwood)

12. A Most Wanted Man (Anton Corbijn)

13. Nightcrawler (Dan Gilroy)

14. The Homesman (Tommy Lee Jones)

15. Under the Skin (Jonathan Glazer)

16. Noah (Darren Aronofsky) *full review coming soon

17. Wild (Jean-Marc Vallee)

18. Calvary (John Michael McDonagh)

19. The 50 Year Argument (Martin Scorsese and David Tedeschi)

20. Ida (Pawel Pawlikowski)

21. Locke (Steven Knight)

22. The Drop (Michael R. Roskam)

23. Joe (David Gordon Green)

24. Love is Strange (Ira Sachs)

25. Enemy (Denis Villeneuve)

21. Locke (Steven Knight)

22. The Drop (Michael R. Roskam)

23. Joe (David Gordon Green)

24. Love is Strange (Ira Sachs)

25. Enemy (Denis Villeneuve)

Other Movies I Loved and Admired:

The Imitation Game (Morten Tyldum)

Night Moves (Kelly Reichardt)

Jersey Boys (Clint Eastwood)

Begin Again (John Carney)

I Origins (Mike Cahill)

Edge of Tomorrow (Doug Liman) *full review coming soon

Snowpiercer (Bong Joon-Ho)

Fury (David Ayer)

The Judge (David Dobkin)

The Imitation Game (Morten Tyldum)

Night Moves (Kelly Reichardt)

Jersey Boys (Clint Eastwood)

Begin Again (John Carney)

I Origins (Mike Cahill)

Edge of Tomorrow (Doug Liman) *full review coming soon

Snowpiercer (Bong Joon-Ho)

Fury (David Ayer)

The Judge (David Dobkin)

Unbroken (Angelina Jolie)

The Theory of Everything (James Marsh)

St. Vincent (Theodore Melfi)

Kill the Messenger (Michael Cuesta)

Frank (Lenny Abrahamson)

Magic in the Moonlight (Woody Allen) *full review coming soon

Big Eyes (Tim Burton)

Rosewater (Jon Stewart)

Exodus: Gods and Kings (Ridley Scott)

Guardians of the Galaxy (James Gunn)

Men, Women and Children (Jason Reitman)

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (Matt Reeves)

Muppets Most Wanted (James Bobin)

The Lego Movie (Phil Lord, Christopher Miller, Chris McKay)

The Skeleton Twins (Craig Johnson)

The Theory of Everything (James Marsh)

St. Vincent (Theodore Melfi)

Kill the Messenger (Michael Cuesta)

Frank (Lenny Abrahamson)

Magic in the Moonlight (Woody Allen) *full review coming soon

Big Eyes (Tim Burton)

Rosewater (Jon Stewart)

Exodus: Gods and Kings (Ridley Scott)

Guardians of the Galaxy (James Gunn)

Men, Women and Children (Jason Reitman)

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (Matt Reeves)

Muppets Most Wanted (James Bobin)

The Lego Movie (Phil Lord, Christopher Miller, Chris McKay)

The Skeleton Twins (Craig Johnson)

Best Director: Richard Linklater, Boyhood

Runner-Ups: Bennett Miller, Foxcatcher; Paul Thomas Anderson, Inherent Vice; David Fincher, Gone Girl; Christopher Nolan, Interstellar; Wes Anderson, The Grand Budapest Hotel; Clint Eastwood, American Sniper; Damien Chazelle, Whiplash; James Gray, The Immigrant

Best Actor: Michael Keaton, Birdman

Runner-Ups: Steve Carell, Foxcatcher; Joaquin Phoenix, Inherent

Vice and The Immigrant; Jake

Gyllenhaal, Nightcrawler; Philip

Seymour Hoffman, A Most Wanted Man; Channing

Tatum, Foxcatcher; Bradley Cooper, American Sniper; Ralph Fiennes, The Grand Budapest Hotel; Ben Affleck, Gone Girl; Matthew McConaughey, Interstellar; Tom Hardy, Locke and The Drop

Best Actress: Marion Cotillard, The Immigrant

Runner-Ups: Rosamund Pike, Gone Girl; Scarlett Johansson, Under

the Skin; Reese Witherspoon, Wild;

Hilary Swank, The Homesman; Felicity

Jones, The Theory of Everything; Amy Adams, Big Eyes; Jennifer Connelly, Noah

Best Supporting Actor: Mark Ruffalo, Foxcatcher

Runner-Ups: J.K. Simmons, Whiplash; Ethan Hawke, Boyhood;

Edward Norton, Birdman; Josh Brolin, Inherent Vice; Robert Duvall, The Judge; Martin Short, Inherent Vice

Best Supporting Actress: Patricia Arquette, Boyhood

Runner-Ups: Emma Stone, Birdman;

Katherine Waterston, Inherent Vice; Rene

Russo, Nightcrawler; Carrie Coon, Gone Girl; Kim Dickens, Gone Girl; Keira Knightley, The Imitation Game; Jessica Chastain, Interstellar; Naomi Watts, Birdman

Best Original Screenplay: Birdman

Runner-Ups: Boyhood, Foxcatcher, Interstellar, Whiplash, The Grand Budapest Hotel, Nightcrawler

Best Adapted Screenplay: Inherent Vice

Runner-Ups: Gone Girl, Wild, A Most Wanted Man, The Homesman, The Imitation Game

Best Original Screenplay: Birdman

Runner-Ups: Boyhood, Foxcatcher, Interstellar, Whiplash, The Grand Budapest Hotel, Nightcrawler

Best Adapted Screenplay: Inherent Vice

Runner-Ups: Gone Girl, Wild, A Most Wanted Man, The Homesman, The Imitation Game